Dear Teachers and Parents,

to learn about the illness and about its potential effect on the child. This online edition of Uveitis: A Guide for Teachers and Parents contains the same information that appears in the published version. We have written this material to provide teachers and parents with information about uveitis and to suggest some guidelines for adapting the classroom and school setting. If you have a question, or would care to comment on our efforts, please post a note on this online forum. Uveitis (U’VE-I-TIS) is a rare, serious medical condition that affects vision. When a child has uveitis, it is important for teachers and for parents

Sincerely yours,

C. Stephen Foster, M.D.

Clinical Professor of Ophthalmology

Harvard Medical School

Click here to purchase a copy of Uveitis: A Guide for Teachers and Parents. Copies are available on Kindle for $2.99 or paperback for $5.50.

Click here to purchase a copy of Uveitis: A Guide for Teachers and Parents. Copies are available on Kindle for $2.99 or paperback for $5.50.

(www.ed.gov/offices/OSERS/Policy/IDEA/regs.html). Special education considerations in the United States include such things as support for modification of assignments or the environment, or for specialized equipment. If the child needs a special computer screen or program, or a scribe, this could be funded under special education.

Children with uveitis whose vision does not interfere with school work may be eligible for accommodations under section 504 of the American with Disabilities Act

Please share this booklet with other school staff so everyone who has contact with this student is aware of his or her abilities and needs. We have found that the parents of children with uveitis are eager to work with school staff to ensure that their children achieve maximum potential, both academically and socially. We recommend, before or soon after the school year begins, that a meeting be held with the student’s parents. Go over the material in this booklet together. Make a plan. Invite any other school staff members who see your student on a regular basis. This may include the principal, PE teacher, vision specialist, and school nurse or bus driver. And, please, ask the parents to alert you to any problems that could affect the child’s performance and attitude. Throughout the school year, inform parents of changes in the child’s physical and emotional health, and urge them to communicate regularly with you, too.

Uveitis (U’VE-I-TIS) is a rare, serious medical condition that affects vision. Uveitis is inflammation deep inside the eye, in the middle layer of the eye that carries the blood supply to other parts of the eye. This middle layer of the eye is called the “uvea” (or uveal tract). Uveitis is like having inflammation from a burn, but inside the eye. Inflammation occurring inside the eye is a medical emergency. If not treated, vision loss will occur.

If you have never heard of uveitis, you are not alone. Uveitis occurs so rarely that it is unlikely your school has had even one other student with this illness. In the United States, for example, it is estimated that 11,500 children have uveitis and that 2,250 new cases are identified every year. Despite how rare it is, uveitis is the third leading cause of preventable blindness in the developed world.

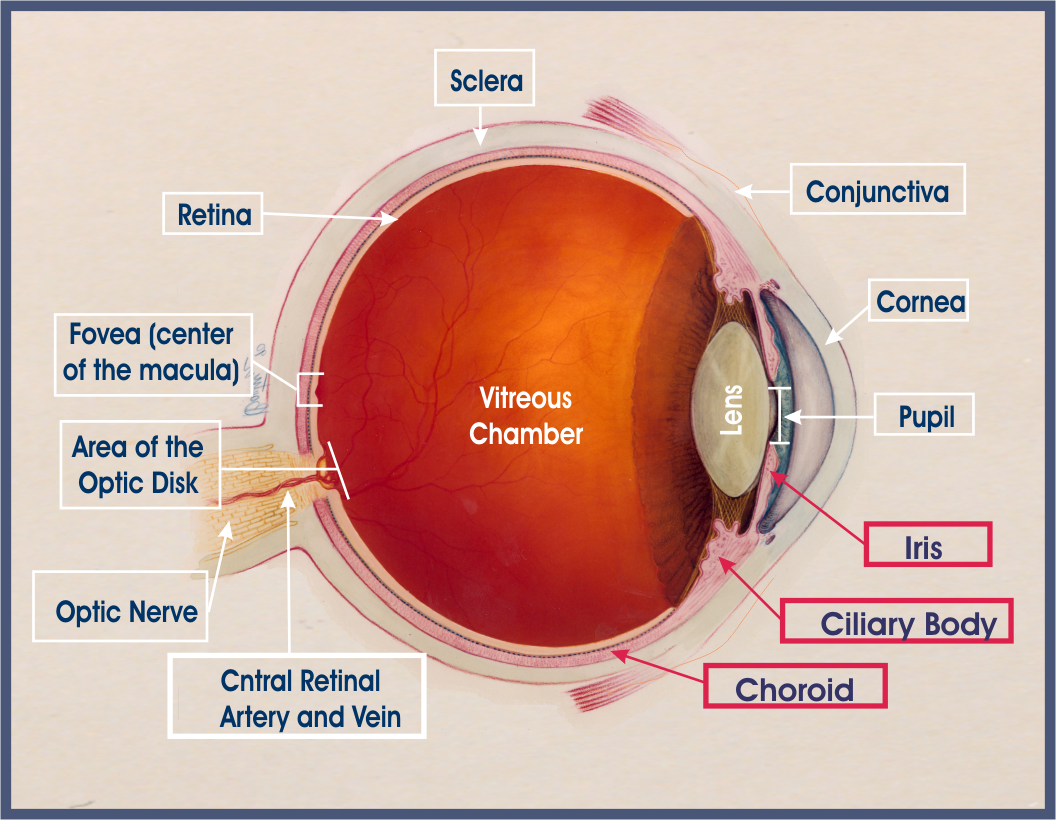

Anatomy

Anatomy

Uvea (u’ve’a) is the Latin word for grape. If you could see the uveal tract, it might remind you of a grape that has had its outer skin peeled away. The uvea is brown and round, with a “stem” formed by the optic nerve. “Itis” is the Latin suffix for inflammation. Put the two words together: uve + itis = “uveitis”. The uvea surrounds the eye like a tunic (coat). The visible part of the uvea is the iris.

The uveal tract has three main parts. The iris gives the eye its characteristic color. It changes shape to control the amount of light entering the eye. The ciliary body makes fluid for the inside of the eye. The choroid is very vascular and provides the blood supply for the eye. Inflammation affecting any of these parts of the eye is called uveitis.

Uveitis is the third leading cause of preventable blindness in the developed world. Despite this, it is a rare disease. Uveitis can develop at any age. It is found in all races and occurs worldwide. It is not contagious. Patients with uveitis starting before the age of 16 years represent 5% to 10% of the all cases of uveitis.

Uveitis has an estimated prevalence of about 38 cases per 100,000 population, and an incidence of 15 cases per 100,000 population. 2,359,242 people in the world are estimated to have the disorder. In the United States it is estimated that uveitis afflicts 109,000 people and that 43,000 new cases are diagnosed each year. It is estimated that, at any one time, about 11,500 children in the United States will have uveitis and that 2,250 new cases are identified every year.

Uveitis symptoms include pain or redness in the eye, sensitivity to light (photophobia), blurred or diminished vision, problems with “glare”, seeing black spots (called “floaters”), and sometimes, abnormal eye movement or alignment. Children with uveitis are at increased risk for developing glaucoma and cataract. Some children with uveitis will become blind. Most children with uveitis will require years of medical treatment in an effort to save their vision. Roughly half of the children with uveitis will not have symptoms to warn them of disease activity. In this instance, the uveitis is usually discovered after there has been irreversible vision loss caused by damage to the retina or optic nerve.

Vision will always be affected when there is inflammation inside the eye. How vision will be affected depends on how severe the inflammation is, how long the inflammation has gone uncontrolled, whether the student is having a “flare” up of symptoms (whether the illness is active or in remission), whether complications such as glaucoma or cataract have developed, and what treatment the child is receiving. As you might imagine, it can get pretty complicated.

Vision will always be affected when there is inflammation inside the eye. How vision will be affected depends on how severe the inflammation is, how long the inflammation has gone uncontrolled, whether the student is having a “flare” up of symptoms (whether the illness is active or in remission), whether complications such as glaucoma or cataract have developed, and what treatment the child is receiving. As you might imagine, it can get pretty complicated.

Vision may fluctuate from relatively “normal” to very poor. Children with uveitis may be able to read with little assistance one month and then may need adaptive text the next. Or, the visual problems may be relatively stable and predictable. Glare can be a big problem inside and out of doors. Communication with the child’s family is crucial to understanding how your particular student is doing and what specific adaptations will need to be implemented.

Children with uveitis whose vision impairment interferes with their ability to do school work qualify for special education considerations under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). (Website: uveitis. It is really hard to go to school and have something that no one has ever heard of! I think all of my teachers so far have understood about my eyes. They didn’t get mad if I would miss class for an eye appointment or anything. I hate it though that none of your friends or any of your classmates know what your talking about. I mean they don’t know what you have to go through everyday with having to put drops in and then eye appointments. It gets kinda of hard. Like when I explain that I have Uveitis no one has ever heard of it. Well I think that is a great idea!” ~ Michelle

Hi Michelle –

Hi Michelle –

I agree with what you said about friends not getting it. Right now my two closest friends are both very smart people so they are able to understand what I’m explaining to them, and to empathize. Friends I’ve had in the past just didn’t really comprehend and would sometimes ask “So are your eyes all better now?” Others would never ask me how my eyes were, as if I didn’t even have a problem. I don’t know which one bothers me more. Probably the ones who didn’t ask me anything at all. ~Em

Classroom Exercise:

The Kids Online Club is open to any student or class that would like to participate. Pre-registration is required to make use of the Club’s safety features.

Uveitis can have a significant impact on the child’s experience at school. In this section we make recommendations about adaptations that may assist students whose vision has been affected by uveitis. These suggestions are equally valuable to employ at school and in the home.

These are general recommendations. An individual educational plan will need to be developed to reflects the student’s specific needs. Consider implementing any adaptations prior to a period when the child may be feeling ill. This will give the student the best chance of continuing his or her routines under difficult circumstances.

Some students with uveitis have additional, non-vision related health problems that may also require consideration.

The extent to which vision is affected by uveitis is different for each child. The complications of uveitis can be obvious, as in the case of severe vision loss, or subtle, as in the instance of a student whose vision has been preserved by treatment with immunosuppressive chemotherapy. Vision may fluctuate widely and be affected by the illness and, sometimes, but the medications used to treat it For example, eye drops make vision blurry.

Students being treated with immunosuppressive chemotherapy may be fatigued or less focused cognitively on some days. Some children experience significant eye pain (photophobia) during illness flares, others do not. Children can feel unwell in a wide variety of ways during a “flare” or during certain phases of treatment. And they can feel very distressed if changes in physical appearance.

Children generally adjust to all of this in some proportion to how the adults around them are handling things. But, kids have questions too. They worry, sometimes, about going blind. They get upset when the adults around them are upset. And, they worry about fitting in at school and especially about “being different”.

Knowing that a teacher is “tuned in” to these fluctuations and is someone to whom the student can turn is the single most valuable resource a student can have at school.

Many students with uveitis will have difficulty accomplishing visually demanding tasks. These are some examples of visually demanding tasks: reading, taking class notes, producing written assignments, using a computer, art projects, playing music, playing board games, looking at a chalk board or electronically projected material, going to a library, playing table games, riding a school bus, reading street signs, going on field trips, and playing baseball or other sports. I am sure that you will be able to think of many other examples at your school.

The school vision specialist (or Vision Rehabilitation Center specialist) can help you determine what materials will benefit your student.

Use Large Print material. Generally, font sizes may need to range from 14 to 20 point.

Seat your student so that light falls onto the work surface from behind (over the shoulder)

For some children, especially in second and third grades, the print itself is large enough, but there may be too much printing on a page, causing ‘visual clutter’, and increasing eye strain and eye fatigue.

Decrease competing background on written materials (make them less “busy”)

Decrease the amount of print on a page

Most class room materials can easily be enlarged with any good photocopier

Use materials that provide extra contrast (e.g. bright colors on light paper, light colors on dark surfaces, yellow or colored chalk on the chalkboard).

Allow the child to hold the book as close or as far away as necessary, even to tilt the book to see better. The child will learn appropriate adaptations as to what is most comfortable to see well. None of these things will ‘hurt’ his or her vision

Use different color “manipulatives” or color coding to help the student find materials or papers more easily

Encourage the student to take frequent breaks from reading or close work

Assess rather it may be necessary to excuse students periodically from homework if there are significant symptoms

Use books on tape, and encourage the student to use them, especially for book reports and projects. These are a beneficial tool to encourage listening skills and listening comprehension. Books on tape help the student to complete reading assignments or prepare for book reports or projects

Students with impaired vision may be able to read the computer more easily if they:

Increase the size of the type

Change the style of the type

Increase the contrast on the screen

Take breaks and rest

Give the student preferential seating for board work as well as placement of materials for computer use or table top tasks.

Encourage the student to approach the board freely as needed or to make other adjustments in the work space

Provide the student with a personal copy of materials written on the board or projected onto a screen or give the student a copy of your notes to use to copy

Adjust room lighting to minimize glare on the board

Many children with uveitis experience an increased sensitivity to glare. Glare can be caused by sunlight, commonly used lighting sources, and reflections from schoolroom surfaces. Reducing glare will improve the student’s ability to see what is on the page or board. Common situations that produce the glare are: fluorescent lighting, having to stare into a bright light while trying to see detail; projectors, cloudy or snowy days, very bright sunshine, oncoming headlights.

The adaptations listed below for reducing glare may also help the student with symptoms of photophobia (light sensitivity). Light sensitivity is a common problem that children experience, especially during times of flare, or if medications are needed to dilate the pupils. When the student is experiencing photophobia, pain can be significant and vision decreases when too much light floods the retina.

Test different kinds and levels of lighting to determine what is most comfortable for your student.

Fluorescent lighting, of all available light types, produces the most glare. Turn off fluorescent lighting if possible. Full spectrum lighting is the closest to natural sunlight and the most comfortable for people with most visual pathologies. Incandescent lighting casts a yellow light. It is the most common form of light bulb, frequently used in desk or table lamps.

Seat your student so that they are not directly facing a window as the glare produced by that cold “wash out’ images. Think of how your vision is reduced when driving a car directly into the setting sun.

Drapes or blinds reduce sunlight coming in through windows. Polarized glass or tinted shades will eliminate glare.

Replace white paper with newsprint or soft green paper to reduce glare from the page. This will improve the student’s ability to see what is on the page. Newsprint is generally available in schools and is inexpensive when compared with white paper.

Glasses can prescribed that filter light to reduce problems with glare. Encourage your student to experiment with colored lens (“sun glasses”) and hats with brims to reduce glare from overhead and outside light.

A piece of yellow acetate over white paper can help decrease the glare from overhead lights on bright white paper

Encourage the student to take frequent breaks from close work (reading, writing, computer work) to reduce eye fatigue

Anticipate that your student may need more time than others to adjust to lighting changes, particularly when coming in from outside or when walking into bright light.

Homework and other assignments may need to be adjusted during an illness flare so that the child’s eyes can be rested

Include homework assignments that can be read to the student, or questions that can be done orally at home.

Allow written assignments to be done using “narration”, where the student narrates to the parent, who writes down what the student says verbatim. Later, the student can re-copy and make revisions.

Children with uveitis should be encouraged to participate in play ground and athletic activities but must, at all times, take special precautions to protect their eyes from injury. One parent’s solution to her daughter’s refusal to wear protective eye gear during soccer was to buy the whole team the same eye gear. Now, all of the kids want to have this “equipment”

ground and athletic activities but must, at all times, take special precautions to protect their eyes from injury. One parent’s solution to her daughter’s refusal to wear protective eye gear during soccer was to buy the whole team the same eye gear. Now, all of the kids want to have this “equipment”

The student with uveitis should ALWAYS wear shatter proof eye glasses or athletic eye shields during playground activity or athletic games where sticks or balls are used or where hard contact is expected.

Injury to an eye can cause the disease to get worse or cause permanent damage to vision.

UV coated sun glasses should be worn on sunny days when outdoors.

If the student’s vision is fluctuating widely, or vision is impaired by glare, students should suspend participation in hard contact sports and not drive a car.

We would be pleased to try to answer questions you may have about uveitis after reading this material, or to direct you to an appropriate resource. To ask a question, please point your web browser to the “Ask Dr. Foster” forum on www.Uveitis.org. Post your question. You will get a reply.

Our online support community has a parent forum. The suggestion to develop this material was proposed there. The parent-members of the forum provided, through their online discussion, valuable insights and suggestions about content. Members of the Uveitis/OID Support Group in Boston coordinated the project and provided subject expertise.

Elizabeth Irvin, PhD

Frances B. Foster, RN, MS, CS

Uveitis/OID Support Group, Cambridge, MA USA

Sharon Ray, ScD, OTR/L

Assistant Professor of Occupational Therapy (Pediatrics)Tufts University Boston School of Occupational Therapy

Mary Anne Roberto

Vision Specialist and Parent-Member (Pennsylvania), Uveitis/OID Support Group

Em and Michelle are student-members of the Uveitis/OID Support Group.Em attends South Side High School in New York and Michelle is a student at Triton High School in Minnesota

Emily Herzlin

is an artist on Long Island. Uveitis Eye(back cover)

Audrey Melanson

is a Medical Photographer at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary. Slit lamp photo.

Set your printer to “portrait” view

Select A4 for the paper size (or, letter, 8.5″ x 11″)

The top, bottom, left and right margins for your printer must each be set to .5″ in order for this file to print properly.

Preview the printed page before printing [FILE > PRINT PREVIEW]. If the Header images (top of the page) displays completely (is not cut off on the right or left) chances are your printer settings are correct.

If images in the header or margins are cut off in the printed version, go into your PRINTER settings and review the margin settings.

We recommend the use of professional services to translate medical and support information on this website. Non-English speaking readers may find that these free online programs are of some assistance in an initial review of this material

We would appreciate learning about translations of this material that we could consider, after review, for posting on this website. If you have such material and are interested in providing it free of charge as a public service, please contact Dr. Foster for details.

National Eye Institute

National Institutes of Health Website: www.nei.nih.govAmerican Uveitis Society

https://www.uveitissociety.org/

Pars Planitis.org

www.parsplanitis.org

![]() This symbol indicates that the material is on another website. We have checked the websites we link to and think they are good. But, website content can change at any time and websites don’t have to tell anyone that they have changed. So, when leaving the Uveitis Kids Page, please be sure to

This symbol indicates that the material is on another website. We have checked the websites we link to and think they are good. But, website content can change at any time and websites don’t have to tell anyone that they have changed. So, when leaving the Uveitis Kids Page, please be sure to

![]() A Big Look at the Eye

A Big Look at the Eye

![]() How Dogs See

How Dogs See

![]() How The Eye Works

How The Eye Works

![]() The Nocturnal Eye

The Nocturnal Eye

![]() Taking a Good Look at Glasses

Taking a Good Look at Glasses

![]() What is 20/20 Vision?

What is 20/20 Vision?

![]() What Visual Impairment is

What Visual Impairment is

![]() Why do People Have Red Eyes in Some Flash Photography?

Why do People Have Red Eyes in Some Flash Photography?

![]() Taking a Good Look at Glasses

Taking a Good Look at Glasses

What is uveitis?

What is a cataract?

Why does the doctor check my eye pressure?

What is a slit lamp?

Why does the doctor check my eye pressure?

What is a slit lamp?

How do blood cells fight disease?

The Kids Club is open to any student or class that would like to participate. Pre-registration is required to make use of the Club’s safety features.

Negotiating the Special Education Maze: A Guide for Parents and Teachers. Anderson, W. , Citwood, S., & Hayden, D. (1997). Negotiating the Special Education Maze: A Guide for Parents and Teachers (3rd ed.). Bethesda, MD.: Woodbine House. 800-843-7323

Children with Low Vision

https://www.low-vision.org

This website gives practical suggestions, appropriate for parents and teachers, for supporting the development of the child with vision challenges. It has material written in English and in Spanish about developing your child’s vision, and a guide for parents of infants and young children with vision impairment. It goes through school age and the the suggestions are practical and easily implemented.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)

Website: www.ed.gov/offices/OSERS/Policy/IDEA/regs.html

Americans with Disabilities Act, Section 504

Website: www.hhs.gov/ocr/504.html

This material is copyrighted by the Ocular Immunology and Uveitis Foundation, C. Stephen Foster, M.D., President. Readers are encouraged to redistribute this material to other individuals for noncommercial use and free of charge, provided that the text, HTML codes, and this notice remain intact and unaltered in any way. Uveitis: A Guide for Teachers and Parents may not be resold, reprinted or redistributed for commercial use or compensation of any kind without prior written permission from the author.

Suggested citations are listed below. If you have any questions about permission, please contact Dr. Foster.

C. Stephen Foster, M.D.

President

Ocular Immunology and Uveitis Foundation

1440 Main Street Suite 201

Waltham, MA 02451

Phone: 781-891-6377| Toll Free: 866-853-6377

Fax: 781-647-1430

Email: fosters@uveitis.org

Web: www.Uveitis.org

Voice: 617-797-1185

EMail: ffoster@mersi.us

Web: www.Uveitis.org

WEB Edition

Foster, C. Stephen. Uveitis: A Guide for Teachers and Parents. Ocular Immunology and Uveitis Foundation, Waltham, Massachusetts USA.

Print Edition

Foster, C. Stephen (2004). Uveitis: A Guide for Teachers and Parents. Ocular Immunology and Uveitis Foundation, 348 Glen Road, Weston, MA. 02493, USA . Revised August 2005.

Index

In this drawing, the eye is viewed from the top

The middle layer of the eye is called the uvea or uveal tract. It is made up of the iris, the ciliary body, and the choroid. The uvea surrounds the eye like a tunic (coat). The visible part of the uvea, in the front, is the iris. Inflammation in any of the parts of the uveal tract is called uveitis. Inflammation inside the eye is a medical emergency because, untreated, it will lead to vision loss. Click here to print a diagram of the eye.

Back to Top of Page | Glossary of Terms

Ocular inflammatory disease (OID) is a general term for inflammation affecting any part of the eye or surrounding tissue. Inflammation involving the eye can range from the familiar allergic conjunctivitis of hay fever to rare, potentially blinding conditions such as uveitis, scleritis, episcleritis, optic neuritis, keratitis, orbital pseudotumor, retinal vasculitis, and chronic conjunctivitis.

Broadly speaking, if inflammation develops in the eye(s), or in the optic nerve, blood vessels, muscles or other tissues that surround the eye, the resulting illness is classified as an ocular inflammatory disease (or OID for short).

The location of the inflammation governs the diagnostic name for the ocular inflammatory disease. For example, uveitis is inflammation in the uveal tract; scleritis is inflammation of the sclera, pars planitis is inflammation of the pars plana, and so forth.

Back to Top of Page | Glossary of Terms

What is inflammation?

Literally speaking, inflammation means setting on fire. Inflammation can develop in any part of the body, including the eyes and their surrounding structures. Inflammation is a characteristic reaction of tissue to injury or disease. Inflammation results from the body’s attempt to eliminate a foreign body or germ and helps to prevent further injury.

Inflammation is marked by four signs: swelling, redness, heat, and pain. You have probably observed the signs of inflammation in a cut or burn on your hand.

Inflammation is a complex process involving many different kinds of white blood cells: granulocytes (neutrophils, basophile, and eosoniphils) and some immune specific white blood cells called B and T lymphocytes along with their antibodies and cytokines. In all inflammatory diseases there is the migration of these specific types of white blood cells out of the bloodstream into surrounding tissues. These cells release agents (chemicals), such as cytokines, to boost immune responses and kill invading bacteria, viruses, and parasites or anything that the immune system perceives as foreign (antigen), or non-self. Part of their response is bringing antibodies (proteins in the family of immunoglobulins) to the site; the antibodies then attach to antigens and mark them for death. Antigens are anything that the immune system recognizes as non-self or foreign and, therefore, trigger an immune response. The linking of the antibody to the antigen forms an immune complex. Immune complexes circulate through the blood. Usually they are removed quickly, but occasionally they are lodged into tissues and cause inflammation.

Normal healthy tissue can be injured by inflammation during this process (innocent bystander injury). When this happens in or around the eyes, the affected region (the eyes, the eyelids, the sclera, the iris, the uvea, the retina, the optic nerve) becomes red, sore, and swollen. This inflammation can be observed by the eye doctor using a slit lamp microscope. If eye inflammation is long lasting (chronic) or severe, damage to delicate tissues and blood vessels in and around the eye can occur, resulting in vision loss.

Back to Top of Page | Glossary of Terms

The immune system is designed to protect and defend the body from foreign intruders (germs). The mechanisms of the immune system reside in the body, not in the eye. The immune system is complex. Essentially, it contains several different types of cells, some of which function like security guards, which are constantly on patrol looking for any foreign invaders. When they spot one, they take action and eliminate the intruder.

In some forms of ocular inflammatory disease, the immune system loses its ability to tell the difference between a foreign intruder and a person’s own normal tissues and cells. So, in essence, the guarding cells lose their memory, and they mistakenly identify the person’s own normal cells as foreign (antigens) and, subsequently, take action to eliminate them.

This dysregulation of the immune system is termed autoimmunity, or immune attack against self. The reason why this happens is unknown. The result of autoimmunity is chronic inflammation.

Back to Top of Page | Glossary of Terms

Autoimmune-mediated Ocular Inflammatory Disease

Autoimmune diseases are characterized by the body’s immune responses being directed against its own tissues, causing prolonged inflammation and subsequent tissue destruction. A number of autoimmune diseases exist, the most familiar of which is rheumatoid arthritis. In rheumatoid arthritis, the dysregulated immune system attacks the joints.

A number of autoimmune diseases exist in which the eye or various parts of the eye may be attacked. In ocular inflammatory disease, often the autoimmune disease is systemic, not only involving the eye but a variety of organs throughout the body. The most common examples of such diseases include rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, polyarteritis nodosa, relapsing polychondritis, Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (formerly called Wegener’s), scleroderma, Behcet’s disease, inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis), sarcoidosis, and ankylosing spondylitis.

However, the eye may in certain instances be the specific and only target affected by certain autoimmune diseases. Some such diseases include ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, Mooren’s corneal ulcer, and some forms of uveitis, including Birdshot retinochoroidopathy, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome, and sympathetic ophthalmia.

Back to Top of Page | Glossary of Terms

Inflammation can affect any part of the eye or its surrounding structures. The symptoms of inflammation for the most part depend on the area in the eye of the inflammation. Most common signs and symptoms are:

Eye pain, severe light sensitivity, and any change in vision are considered emergency signs and need immediate attention by an ophthalmologist.

Back to Top of Page | Glossary of Terms

The forms of ocular inflammatory diseases that are most commonly seen include ocular allergy, cicatricial pemphigoid, scleritis, peripheral ulcerative keratitis, retinal vasculitis, chronic conjunctivitis, and anterior, intermediate, and posterior uveitis. OID occurs throughout the world. There are over 85 causes of uveitis/OID. They can be infectious or noninfectious, traumatic, drug-induced, or malignant. Both women and men of any race, ethnicity, or age may develop OID.

Infectious causes may be bacteria, parasites, fungus, viruses such as rubella, HIV; sexually transmitted diseases such as syphilis, Chlamydia, or gonorrhea; or rare infections, such as tuberculosis, toxoplasmosis, or Lyme disease.

There are several causes of noninfectious OID, one of which is autoimmune disease. In many cases, the autoimmune disease is systemic (affecting the body) and, also, produces inflammation in specific parts of the eye. The ocular inflammatory disease will then be identified according to that part of the eye which has inflammation. For example, juvenile rheumatoid (or idiopathic arthritis) is associated with inflammation in the anterior part of the eye, known as anterior uveitis or iritis. The area of inflammation in the eye also is helpful to the doctor in the development of differential diagnoses to detect the cause of your OID.

Autoimmune diseases can also affect just the eye; such as in the following ocular diseases: Birdshot retinochoroidopathy, Fuchs’ heterochromic iridocyclitis, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada, ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. The other cause of noninfectious OID is termed idiopathic. Idiopathic OID is basically a diagnosis of exclusion. That is, no infection or associated systemic illness can be identified at the time of the diagnosis of eye inflammation. In this instance, inflammation is located entirely in the eye or its structures. This form of OID does not tend to have blood tests that can be used to follow the disease course. The inflammation is evaluated by the doctor using the slit lamp.

Drug or medication can also be the cause of ocular inflammatory disease. Some drug examples are bisphosphonates, cidofovir, rifabutin, and sulfonamides or topical corticosteroids and latanoprost. Vaccines and even skin tattoos can be inducers of OID. Certain cancers can cause ocular inflammatory disease, such as lymphoma, lung cancer, and breast cancer.

Back to Top of Page | Glossary of Terms

Itis is the Greek suffix for inflammation. This suffix is often combined with the name for the part of the eye that has the inflammation to describe the illness.

So, a person may be said to have iritis (IRIS + “itis” =I’RI-TIS) when the colored part of the eye (the iris) has inflammation. The term scleritis is used, broadly, to describe inflammation of the sclera (SCLER-I’TIS), the tough white outer coat of the eye. Uveitis is inflammation of the uveal tract, the middle layer of the eye (U’VE-I’TIS).

Inflammation of the retina will be broadly described as retinitis. If the vasculature is involved, then it is called retinal vasculitis. Inflammation in the optic nerve is termed optic neuritis. Cornea inflammation is keratitis and conjunctival inflammation is conjunctivitis. If both are involved, it is keratoconjunctivitis.

While this naming convention does not hold true for all inflammatory eye diseases, it helps to explain why there are so many different names for ocular inflammatory disease.

Back to Top of Page | Glossary of Terms

Usually, when an eye problem is suspected, a patient is first sent to a general, comprehensive ophthalmologist. He or she will

perform a thorough eye exam, including:

Because ocular inflammatory disease can be caused by so many different things, diagnosis may require a referral to a specialist (an Ocular Immunologist) for further diagnostic evaluation and treatment.

The ocular immunologist will review the following, along with his or her exam, to help make the diagnosis:

Back to Top of Page | Glossary of Terms

The treatment of ocular inflammatory disease is aimed at eliminating inflammation. This in return will alleviate pain, stop formation of new floaters, and normalize any acute changes in vision. It is crucial to stop the inflammation before delicate tissues in the eye are damaged in order to prevent secondary complications and permanent vision loss. The goal of treatment is prevention of recurrence without chronic use of steroids. This goal can be reached by using a treatment stepladder approach explained next. The long-term goal is total remission of the ocular inflammatory disease, off of all medication. The road to remission can be bumpy as some forms of ocular inflammatory disease can be very aggressive and “stubborn” to control.

In understanding the treatment of OID, one has to remember that the mechanisms of the immune system reside in the body, not in the eye. The treatment of OID is aimed at the cause when it is identifiable. If you have an infection, your doctor will prescribe antibiotics.

For noninfectious causes of inflammation, including idiopathic, treatment will follow a stepladder approach. The object of the stepladder approach is to modify the immune system, to stop it from inappropriately attacking the eye and causing inflammation.

The first step is steroid medication. A steroid is an anti-inflammatory immunosuppressive medication that can be administered in many forms: drops, oral, injection, or intravenous infusion. The form of steroid that is prescribed depends on the severity and type of OID one has. Steroid is an effective medication in quickly aborting acute inflammation, but used long-term, it results in its own set of complications, such as stomach ulcer, osteoporosis (bone thinning), diabetes, cataract, glaucoma, cardiovascular disease, weight gain, fluid retention, and Cushing’s syndrome.

If inflammation continues to recur after weaning off of steroids, your doctor will move to the next step, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS). Some examples of NSAIDS include Motrin, Celebrex, or Naprosyn. NSAIDS are a nonsteroidal type of medication aimed at suppressing inflammation. Oral NSAIDS require monitoring of your liver and kidney function. Certain types of oral NSAIDS, if used long-term, will need added medication for protection against stomach ulcers.

When inflammation persists despite the use of an NSAID, the next approach in the stepladder is immunosuppressive chemotherapy medications or immunomodulatory therapy (IMT), such medications include, Methotrexate, CellCept, Imuran, Cytoxan, Leukeran and Cyclosporin. Your doctor will always start with the type that he or she believes is most appropriate for you and your type of OID. In addition, the medication which has the least potential for side effects is favored. The use of such medication requires special, regular monitoring (blood tests) in order to ensure that no hidden side effects are creeping in. Regrettably, many people (including a surprising number of physicians) are unaware of the very favorable risk-to-benefit ratio of such medications used in the doses that rheumatologists, ocular immunologists, and other specialists prescribe for immunomodulation of autoimmune disease. As a result, many people equate the use of such medicine with the high doses given in cancer chemotherapy, with all the risks and side effects that occur at these high doses.

This is not at all what IMT for OID is all about. Used correctly, by a physician who is an expert in such matters, the patient with OID who is treated with IMT should look and feel normal. If an IMT medication disagrees with a patient, that medication should be stopped, and another tried, so that the goal of no inflammation on no corticosteroids and no significant IMT side effects is achieved.

A newer category of medications employed for the treatment of autoimmune diseases called biologic response modifiers (BRM) or biologics exists. The biologics more specifically target certain elements of the immune system and, in so doing, avoid some of the potential risks of the more conventional IMT medications. Such medications include Enbrel, Humira, Remicade, Zenapax, Orencia, Rituximab, and Immunoglobulin (IgG).

A BRM medication may be added to a conventional IMT medication in the stepladder approach in aggressiveness of therapy for stubborn inflammation. The only double masked, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial for any of the BRM medications performed to date was conducted by Dr. Foster using Enbrel from the TNF-alpha antagonist drug class. The conclusion of this study was that Enbrel was ineffective in modifying recurrences of uveitis. The clinical experience at MERSI by Dr. Foster and elsewhere, however, is that the other two TNF-alpha antagonists, Humira and Remicade, can, in certain patients, have a favorable influence on ocular inflammation.

It should be noted here that none of the medications mentioned in this pamphlet, including corticosteroids, IMT and BRM medications, is approved for treating OID by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA). That is to say, the pharmaceutical companies who manufacture these medications have never conducted the randomized clinical trials required by the FDA in order for the companies to include treatment of OID in the package insert or “label” for the medication. Therefore, doctors who employ such medications for treating OID do so “off-label.” Off-label use is perfectly legal and appropriate, if, in the doctor’s opinion, it is in the patient’s best interest to proceed with such treatment. One can find in the medical literature many clinical reports in the success of the use of these types of medications mentioned above.

In addition to immunosuppressants or antibiotics, other medication may be used. Eye drops that dilate the pupil may be prescribed, if inflammation is in the iris, to prevent spasm of the muscles of the iris and ciliary body that cause pain. Your doctor may recommend sunglasses because bright light may cause discomfort.

Additional treatment may also be required for complications of OID, such as glaucoma and macular edema.

Back to Top of Page | Glossary of Terms

The duration of treatment varies person to person and depends on the type and cause of ocular inflammatory disease. Simple forms of uveitis, for example, may respond to treatment within days and may not recur. Chronic (long-term, recurring) forms of ocular inflammatory disease that threaten vision can be very difficult to cure and require persistence on the part of the treating physician(s) and patient. The length of time required to get the disease into a durable remission on IMT is difficult to quantify and is very individualistic, but a minimum of two years is a reasonable estimate. During treatment on IMT, one can expect visits to the ophthalmologist every 4-6 weeks approximately.

With appropriate, targeted treatment, most people with ocular inflammatory disease will become well-controlled and progress to remission. Once in remission from ocular inflammatory disease, you should expect to have regular follow-up visits to your doctor to make sure that the disease remains in remission.

Back to Top of Page | Glossary of Terms

What kind of doctors treat OID?

It may be apparent after reading this material that doctors who treat ocular inflammatory disease must have special training in both ophthalmology and in ocular immunology. This type of specialty training is accomplished at an advanced level and is termed Fellowship training. Doctors with this training are specialists in Ocular Immunology, the immunology of the eye, as well as comprehensive ophthalmology. Ocular immunologists, because of their specialty training, are better able to hunt for the cause of your ocular inflammatory disease. Such specialists apply the principles of diagnosis of ocular inflammatory disorders in order to initiate appropriate, disease-directed evaluations. It is the cause of the OID, whether idiopathic or not, that directs treatment.

The training of the ocular immunologist also provides him or her with knowledge and experience in the use of the stepladder approach to care. The ocular immunologist is also experienced in knowing when one needs to switch from one IMT to another, how to prevent any potential side effects through close monitoring, and manage side effects if they occur. Furthermore, Ocular Immunologists have special skills with regard to the surgical management of ocular inflammatory disorders.

Back to Top of Page | Glossary of Terms

Ocular inflammatory disease is a serious illness that affects vision. Because it is a rare illness, you may not know others with your same problem, and you and your family and friends will need to learn about your illness and its treatment.

How people react to serious illness depends on many conditions. Three deserve note. The first is the severity of the illness. Your vision has been affected and you may not feel well in other ways; aggressive medical treatment may be required to save your vision. It is not uncommon to feel distressed in the face of the many decisions that must be made, often quickly. This is quite natural. Ask questions and ask for information.

The second is what social support you have available; if you are willing to ask for help and you have a wide support network, you will have an easier time than if you are isolated. The third condition is your personality; if you have always been pretty resilient, you are likely to have resilience in coping with the illness.

This booklet was developed to provide you with information about your illness. This is an important tool in your recovery. Get informed; learn about your illness. Be a participant in your care.

You and your family may find that you also need support and information in an ongoing way, and the Uveitis/Ocular Inflammatory Disease Support Group offers free services and programs just for you. Ask any staff member about these resources, or look here on the website for more information. Coping with a serious illness such as ocular inflammatory disease means reaching out to others. No question is too small; you are not alone. Consider joining the support group; attend a meeting; get involved! Learn coping skills. It will change your experience with this rare illness.

The Support Group is an educational resource of the Ocular Immunology and Uveitis Foundation (OIUF). The Foundation is the nation’s leading non-profit voluntary health organization dedicated to finding the causes and cure for uveitis and other ocular inflammatory diseases and is the only national organization exclusively serving individuals, families and friends affected by uveitis. OIUF is a non-profit organization based at the Massachusetts Eye Research and Surgery Institute in Waltham, Massachusetts.

Back to Top of Page | Glossary of Terms

Does stress trigger OID?

We do not know for certain. There are many anecdotal reports (personal accounts) of patients flaring during or after a stressful time, but this question requires further scientific study. Although there is no scientific evidence to prove it, we believe that it is possible that certain kinds of stress may play a role in triggering flares of ocular inflammatory disease. Stress does not cause the illness itself, but stress is known to modify how the immune system functions. This has implications for stirring up all inflammatory illnesses, including ocular inflammatory disease.

Are flares related to hormones?

Some women notice each time their inflammation flares up, that the episode invariably occurs at the same point in their menstrual cycle, suggesting that certain hormone level changes can be associated with flare ups. It has been noted that OID improves for many during pregnancy. Shanghvi et al postulated that the rapid withdrawal of the anti-inflammatory effects of estrogen and/or progesterone in the late luteal phase may explain the increase in inflammatory attacks during late menstrual cycle.

Menstrual cycle and uveitis [Related Articles]

Are there any medications that people with ocular inflammatory disease should avoid?

There are no absolute contraindications to needed medications for a person with ocular inflammatory disease. Your doctor should watch for allergic reactions to medications. When taking estrogen or oral contraceptives, you should watch for any connections with a change or increase in flare ups. Some medications can cause uveitis as aforementioned in the “Causes of OID” section and one should be monitored. There have been no randomized, clinical trials done to date on herbal remedies and treatment of OID. If one is taking medication to suppress the dysregulated immune system, then herbal remedies used to stimulate the immune system would be contraindicated.

Does the Ocular Immunology and Uveitis Foundation conduct research?

Yes. The Foundation is the nation’s leading non-profit voluntary health organization dedicated to finding the causes and cure for uveitis and other ocular inflammatory diseases The majority of support for research comes through tax deductible donations received from patients and other friends of the Foundation. The Foundation is also the recipient of research grants from NIH and industry.

Back to Top of Page | Glossary of Terms

National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health

Website: www.nei.nih.gov

Ocular Immunology and Uveitis Foundatio

Website: www.Uveitis.org

Massachusetts Eye Research and Surgery Institute (MERSI)

Website: www.MERSI.com

Glossary of Visions Terms, with Special Reference to Ocular Inflammatory Disease

Website: www.uveitis.org/patients/education/glossary

Back to Top of Page | Glossary of Terms

Resources for Kids and ParentsWebsite: www.uveitis.org/kids/ Uveitis/OID Support Group Uveitis Online Support Group Links to the Medical Literature

|

Back to Top of Page | Glossary of Terms

For an complete, illustrated glossary of terms, with links to the medical literature, please click here. The following are terms used in this file:

Band keratopathy: A deposit of calcium in the cornea. This pathology can be associated with degenerative corneal disease, high blood calcium levels, juvenile uveitis, and chronic uveitis.

Birdshot retinochoriodopathy (BSRC): A chronic intraocular inflammatory disease affecting mainly the back (posterior) part of the eye. BSRC is distinct from other forms of posterior uveitis that have a strong association with the HLA-A29.2 antigen. Its etiology remains unknown. An autoimmune mechanism is likely to play an important pathogenic role.

Blepharitis (anterior blepharitis, posterior blepharitis): An inflammation in the oil glands of the eyelid that results in a chronic or long term inflammation of the eyelids and eyelashes. Symptoms include swollen eyelids and excessive crusting of the eyelashes, most evident in the morning. Tenderness of the eyelids and a foreign body sensation in the eye may occur as well.

Blind spot: Any gap in the visual field corresponding to an area of the retina where no visual cells are present is referred to as a blind spot. There is a naturally occurring blind spot where the optic nerve exists the eye.

Cataract: Protein in the lens of the eye progressively clumps together and clouds the lens, causing a cataract. A cataract can be congenital or develop naturally with aging or can be secondary to chronic inflammation and/or chronic use of steroids.

Cells: The term “cells”, as used to in ophthalmology, generally refers to a collection of white blood cells (leukocytes) in the anterior chamber of the eye. Cells can be observed on slit lamp examination floating in the fluid in the front of the eye. The amount of white blood cells is the measure of uveitis activity, and is scaled from 1 to 4, depending on the severity, (1 being the least severe inflammation and 4 being the most severe inflammation). Illustrated OID Glossary

Inflammatory cells can also accumulate in the vitreous. This occurs as a result of inflammation in intraocular structures such as the ciliary body, retina, and choroid. Cells in the vitreous can be living or dead, and both can become immutably affixed to vitreous fibers. Only live, active cells are graded in the MERSI rating system. Vitreous cells are rated on a scale of 1-4.

Choroid (KOR-oyd): The choroid is a soft, thin, brown, extremely vascular middle layer of tissue that lies between the retina and sclera. It is composed of layers of blood vessels that nourish the back of the eye. Inflammation of the choroids is called choroiditis (KOR-oyd-itis).

Ciliary body: The structure behind the iris responsible for making aqueous humor, the fluid in the front chamber of the eye that nourishes the lens and cornea. The ciliary body is divisible into two parts: the pars plana and the pars plicata anteriorly. The ciliary body is part of the uveal tract. Cyclitis is inflammation of the ciliary body.

Conjunctiva (KAHN-junk-TY-vuh): The conjunctiva is the thin, transparent tissue that covers the outer surface of the eye. It begins at the outer edge of the cornea, covering the visible part of the white part of the eye (the sclera), and lines the inside of the eyelids. The conjunctiva also secretes oils and mucus that moisten and lubricate the eye. Conjunctivitis is an inflammation of the conjunctiva.

Cornea (KOR-nee-uh): The cornea is the outer, transparent, dome-like structure that forms the anterior most part of the outer coat of the eye. Looking through the cornea, as through a window, one can see the iris, pupil, and anterior chamber. The cornea is part of the eye’s focusing system. Keratitis is inflammation of the cornea.

Corneal ulcer: See Keratitis

Cyclitis: See ciliary

Dry eyes, Keratoconjunctivitis Sicca (KCS): Dry eye syndrome is caused by an alteration in one’s natural tear film, a thin layer of tears protecting the surface of our eyes. Damage to the surface of the eyes (cornea and conjunctiva) is responsible for the symptoms of dry eyes which may include irritated, scratchy, dry, uncomfortable or red eyes, a burning sensation or feeling of something foreign in your eyes and blurred vision. Excessive dry eyes may damage eye tissue, scar the cornea, and impair vision and make contact lens wear difficult.

Epiretinal membrane (ERM), Macular Pucker: An epiretinal membrane is a thin layer of collagen on the surface of the retina. It may occur spontaneously. It may occur because of inflammation (uveitis), and may occur after vitrectomy. It usually occurs on or near the macula, and therefore affects vision. If it is extremely thin, some call it a “cellophane maculopathy”. If it contracts, it distorts the photoreceptors or light-sensing neural elements of the macula, producing “macular pucker”.

Episcleritis: See sclera

Eyelids: The eyelids are composed of an outer layer of skin, a middle layer of muscle and tissue that gives them form, and the inner layer of conjunctiva. The eyelids play a key role in protecting the eye’s surface by spreading moisture (tears) over the surface of the eyes through blinking.

Flare: Flare is protein in the anterior chamber caused by leakage from inflamed blood vessels in the iris. It is not always a measure of inflammation. Flare is measured on a scale from 1 to 4, with 4 being the most severe. Flare becomes chronic after inflammation has produced permanent changes to blood vessels, and so “flare” may be present even when the patient is not having a “flare-up” of inflammation. Flare in the vitreous can also be observed and rated.

Floaters: Floaters appear as gray or black specks, strands, or “cobwebs” in front of the eyes. As the eyes move, the floaters move too. Floaters are caused by particles, such as white blood cells and vitreous condensates, suspended in the vitreous gel, the clear, jelly-like fluid that fills the inside of the eye. The floaters cast shadows on the light sensitive retina. It is actually the shadow of the floater that you see.

Fuchs’ heterochromic iridocyclitis: A chronic, unilateral anterior uveitis characterized by iris heterochromia, a condition in which one eye is a different color from the other. The uveitis typically occurs in the lighter colored eye of a young adult.

Glaucoma: Glaucoma is a condition characterized by vision loss due to irreversible damage to the retina and optic nerve from an imbalance between the blood flow and the pressure in the eye. In most instances, this imbalance of forces occurs as a result of pressure in the eye that is too high. Although normal pressure is usually between 12-21 mm Hg, a person might have glaucoma even if the pressure is in this range.

HLA-B27 associated uveitis: HLA-B27-associated uveitis occurs, we think, as a result of some germ or other triggering an autoimmune response. Certain germs have proteins that “look” like part of the HLA-B27 protein that is present on the surface of the cells of the body in patients who inherit the HLA-B27 gene. And if such a person has the bad luck to come into contact with one of those certain germs at some point in life, the person’s immune system will, of course, attack and kill the germ; but it may also then inappropriately begin to “see” part of the HLA-B27 protein as also being foreign or germ-like, and attack it too, producing damage to the patient’s own cells.

Idiopathic: When the ocular inflammatory disease cannot be associated, at the time of evaluation, with a particular systemic illness, it is said to “idiopathic”.

Intraocular pressure (IOP): A measure of the pressure inside the eye; normal IOP varies among individuals. Intraocular pressure is measured using a tonometer.

Iris: The iris is the most anterior part of the uvea. It is the colored ring of tissue suspended behind the cornea and immediately in front of the lens. It regulates the amount of light entering the eye by adjusting the size of the pupil. When we say that someone has green, or brown, or blue eyes, we are describing the color of the iris. Iritis is inflammation predominantly located in the iris.

Iridocyclitis is a term used to denote inflammation in two parts of the uveal tract of the eye; the iris and the ciliary body.

Keratitis, peripheral ulcerative Keratitis: Keratitis is inflammation of the cornea, the outer, transparent, dome-like structure that forms the anterior most part of the outer coat of the eye. If ulcers develop in the peripheral cornea, it is referred to as peripheral ulcerative Keratitis.

Keratic precipitates (KP): Clumps of white blood cells deposited onto the back of the cornea

Lacrimal gland (LAK-rih-mul): The small almond-shaped structure that produces tears; located just above the outer corner of the eye, behind the eye lid.

Lens: The transparent, double convex (outward curve on both sides) structure suspended between the aqueous and vitreous. It is part of the eye’s focusing system. The lens is made mostly of water and protein. The protein is arranged to let light pass through and focus on the retina.

Macula (MAK-yoo-luh), Fovea: The macula is located roughly in the center of the retina, temporal to the optic nerve. It is a small and highly sensitive part of the retina responsible for detailed central vision. The fovea is the very center of the macula that provides the sharpest vision.

Macular edema, Cystoid Macular Edema (CME): When the the macula accumulates fluid, it tends to swell like a sponge. This swelling occurs in tiny grape-like clusters and looks like a cyst, hence the name cystoid macular edema (CME). CME can cause permanent loss of central vision if not properly treated.

Multifocal choroiditis and Panuveitis: Multifocal choroiditis and panuveitis (MCP) is a posterior chorioretinal inflammatory disease of unknown etiology with prominent elements of vitritis and anterior segment uveitis. MCP is more often resistant to treatment with systemic and regional steroids. Immunosuppressive treatment has been found to be effective.

Neovascularization: In proliferative retinopathy, new, fragile blood vessels grow on the surface of the retina and on the optic nerve. These new blood vessels are called neovascularization, and can lead to serious vision problems, because the new vessels can break and bleed into the vitreous. In addition, abnormal blood vessels can grow on the iris, which can lead to glaucoma.

Ocular allergy: The terms “ocular allergy” and “allergic conjunctivitis” are used synonymously because the large majority of eye allergies involve the conjunctiva. The clinical presentation of the various forms of allergic conjunctivitis can be mild to severe with vision-threatening complications.

Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid (OCP): A systemic autoimmune disease. Mounting evidence supports the concept of immunoregulatory dysfunction: antibodies are directed against the basement membrane zone (BMZ) of the conjunctiva and other mucous membranes derived from stratified squamous epithelia and occasionally the skin. OCP is a vision threatening illness that usually requires treatment with immunosuppression.

Optic nerve, optic disc, optic nerve head: The circular area (disc) where the optic nerve connects to the retina. The brain receives information from the optic nerves for the left visual field and the right visual field. Optic neuritis is inflammation of the optic nerve.

Pars plana: The pars plana is part of the ciliary body. The ciliary body is divisible into two parts: the pars plana and the pars plicata anteriorly. Pars planitis is inflammation of the pars plana, a part of the ciliary body.

Pars planitis is one form of intermediate uveitis where some physicians may use the term intermediate uveitis, instead of pars planitis.

Peripheral Vision (per-IF-ur-al): Side vision. The ability to see objects and movement outside of the direct line of vision.

Pupil: The pupil is the adjustable opening at the center of the iris that allows varying amounts of light to enter the eye. The pupil appears dark because the inside of the eye has no light.

Retina: The retina is the light-sensitive layer of nerve tissue that lines the rear two-thirds of the eye. The retina converts images from the eye’s optical system into electrical impulses sent along the optic nerve to the brain. The retina contains one million photoreceptors that capture light rays and convert them into electrical impulses. These impulses travel along the optic nerve to the brain where they are turned into images. There are two types of photoreceptors in the retina: rods and cones. Retinitis is inflammation of the retina. See UVEITIS; POSTERIOR UVEITIS.

Retinochoriodopathy: Pathology or abnormality of retina and choroids.

Sclera (SKLEH-ruh): The tough, white, outer layer (coat) of the eyeball made up of connective tissue fibers. With the cornea, it forms the outer wall or coat of the entire eyeball. Six tiny muscles connect to the sclera around the eye and control the eye’s movements. The optic nerve penetrates the sclera at the very back of the eye. The sclera is covered by the episclera, a thin layer of tissue containing many blood vessels that nourish the sclera. At the front of the eye, the episclera is covered by the conjunctiva. Episcleritis, inflammation of the episclera, is usually mild and rarely progresses to scleritis, inflammation of the sclera.

Superficial punctate keratitis (SPK): A condition in which cells on the surface of the cornea are inflamed. The cause may be a viral infection, a bacterial infection, dry eyes, exposure to ultraviolet light (sunlight, sunlamps, or welding arcs), irritation from prolonged use of contact lenses, or irritation from or an allergy to eye drops. The condition can also be a side effect of certain drugs taken internally, such as vidarabine.

Synechiae (SIN-eeky-eye): Adhesions of the iris to the lens (posterior synechiae) or to the back of the corneal periphery (peripheral anterior synechiae). Focal adhesions will result in an irregularly shaped pupil and may produce secondary angle closure glaucoma due to relative pupillary block.

Tears: The function of tears is to bathe, lubricate, and nourish the surface of the eye. Tears also contain antibodies that help protect the eye from infection. Tears are produced by the lacrimal (tear) glands, located near the outer corner of the eye. The fluid flows over the eye and exits through two small openings in the eyelids (lacrimal ducts); these openings lead to the nasolacrimal duct, a channel that empties into the nose.

Trabecular meshwork (truh-BEC-yoo-lur): The trabecular meshwork is the spongy, mesh-like tissue surrounding the iris that allows the aqueous fluid (humor) to flow to Schlemm’s canal then out of the eye through ocular veins. See Glaucoma.

Uvea (Uveal tract) (YOO-vee-uh): The uvea (from the Latin, uva or grape) is composed of iris, ciliary body, and choroid. Each of these components of the uvea has a unique histology, anatomy, and function. The choroid is the intermediate of the three coats of the eyeball, sandwiched between the sclera and the retina. Anteriorly, the iris controls the amount of light that reaches the retina, whereas the ciliary body is responsible for aqueous humor production.

Uveitis: Uveitis is inflammation inside the eye, specifically affecting one or more of the three parts of the eye that make up the uvea: the iris (the colored part of the eye), the ciliary body (behind the iris, responsible for manufacturing the fluid inside the eye) and the choroid (the vascular lining tissue underneath the retina). Uveitis is the third leading cause of blindness in the developed world.

Anterior uveitis: Inflammation in the front (anterior) part of the eye, in the area between the cornea and the iris. This inflammation derives primarily from inflammation of the iris.

Intermediate uveitis: A term used to denote an idiopathic inflammatory syndrome mainly involving the anterior vitreous, peripheral retina, and ciliary body, with minimal or no anterior segment or chorioretinal inflammatory signs.

Posterior uveitis: Inflammation predominately located in the posterior vitreous, retina, and/or choroid. Posterior means rear or back. Posterior uveitis is a vision disorder characterized by inflammation of the layer of blood vessels underlying the retina, and usually of the retina as well.

Panuveitis: When inflammation is located in multiple parts of the same eye (anterior, intermediate, and posterior sections), it is classified as panuveitis.

Vasculitis: Vasculitis is inflammation in the blood vessels. It may occur throughout the body. When inflammation occurs in the blood vessels of the retina, it is referred to as retinal vasculitis.

Vitreous (VIT-ree-us): The transparent, colorless, that fills the space between the lens of the eye and the retina lining the back of the eye. It contains very few cells, no blood vessels, and 99% of its volume is water. Unlike the fluid in the front of the eye (aqueous fluid) which is continuously replenished, the gel in the vitreous chamber is stagnant. Therefore, if cells or other byproducts of inflammation get into the vitreous, they will remain there unless removed surgically with a vitrectomy.

Vogt-Koyanagi Harada (VKH): Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome (VKH), formerly known as uveomenigitic syndrome is a systemic disorder involving multiple organ systems, including the ocular, auditory, nervous, and integumentary (skin) systems. Severe bilateral panuveitis associated with subretinal fluid accumulation is the hallmark of ocular VKH.

Zonules: The fibers that hold the lens suspended in position and enable it to change shape during accommodation. Zonules attach to the ciliary body.

Back to Top of Page | Glossary of Terms

We would be pleased to try to answer questions you may have about ocular inflammatory disease after reading this material, or to direct you to an appropriate resource. To ask a question, please point your web browser to the Ask Dr. Foster forum. Post your question. You will get a reply.

Back to Top of Page | Glossary of Terms

We recommend the use of professional services to translate medical and support information on this website. Non-English speaking readers may find that these free online programs are of some assistance in an initial review of this material

We would appreciate learning about translations of this material that we could consider, after review, for posting on this website. If you have such material and are interested in providing it free of charge as a public service, please contact Dr. Foster for details.

Back to Top of Page | Glossary of Terms

This material is copyrighted by the Ocular Immunology and Uveitis Foundation, C. Stephen Foster, M.D., President. Readers are encouraged to redistribute this material to other individuals for noncommercial use and free of charge, provided that the text, HTML codes, and this notice remain intact and unaltered in any way.

A Guide to Ocular Inflammatory Disease may not be resold, reprinted or redistributed for commercial use or compensation of any kind without prior written permission from the author.

Suggested citations are listed below. If you have any questions about permission, please contact Dr. Foster.

Back to Top of Page | Glossary of Terms

C. Stephen Foster, M.D.

President

Ocular Immunology and Uveitis Foundation

1440 Main Street, Suite 201

Waltham, MA 02451 USA

Office: 781-891-6377 | Toll Free: 866-353-6377

Fax: 781-647-1430

EMail: fosters@uveitis.org

Web: www.uveitis.org

Uveitis/OID Support Group

Voice: 617-797-1185

Email: USG@comcast.net

Web: www.Uveitis.org/patient/support/

Back to Top of Page | Glossary of Terms

WEB Edition

Foster CS, Foster FB, Irvin EA. A Guide to Ocular Inflammatory Disease. Ocular Immunology and Uveitis Foundation, Waltham, MA USA. www.uveitis.org/patients/support/family,

Print Edition

Foster CS, Foster FB, Irvin EA. (2006). A Guide to Ocular Inflammatory Disease. Ocular Immunology and Uveitis Foundation, 1440 Main Street Suite 201, Waltham, MA 02451 .

Back to Top of Page | Glossary of Terms

Click here to purchase a copy of A Guide to Ocular Inflammatory Disease. Copies are available on Kindle for $2.99 or printed for $7.50.

This section is designed to help you search the medical literature using the resources of the National Library of Medicine. Use the links below to brose the medical literature on autoimmune uveitis and its treatment, or create your own searches by going to www.PubMed.gov

This section is designed to help you search the medical literature using the resources of the National Library of Medicine. Use the links below to brose the medical literature on autoimmune uveitis and its treatment, or create your own searches by going to www.PubMed.gov

Autoimmune uveitis is a treatable condition that may require the use of systemic immunomodulatory medication to halt it’s progression. Although corticosteroids remain the primary initial treatment for patients with uveitis, use of non-corticosteroid immunomodulatory agents in selected patients with uveitis allows for improved control and decreased risk of corticosteroid-induced side effects. A new paradigm for treating ocular inflammation has been pioneered by C. Stephen Foster, M.D. at Harvard Medical School and the Ocular Immunology and Uveitis Foundation. This treatment paradigm is based on a limited tolerance to corticosteroid use and a more proactive approach to cor ticosteroid-sparing immunomodulatory therapy in an effort to induce a durable remission of ocular inflammatory disease off all corticosteroids.

ticosteroid-sparing immunomodulatory therapy in an effort to induce a durable remission of ocular inflammatory disease off all corticosteroids.

Lit search: Uveitis

Review article: Immunosuppressive Drug Therapy in Uveitis

Lit search: Immunomodulatory treatment (IMT)

Lit search: Biologics

Lit search: Enbrel (this medication is not recommended for treatment of uveitis)

Lit search: Remicade (Infliximab)

Lit search: Methotrexate

Lit search: CellCept (Mycophenolic acid or mycophenolate)

Lit search: Chlorambucil (Leukeran)

Lit search: Corticosteroids

Lit search: Cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan, Neosar)

Lit search: Cyclosporine

Lit search: Daclizumab (Zenapax)

Lit search: Humira (Adalimumab)

Lit search: Intravenous immunoglobulin (gamma globulin, IgG, IV-IgG)

Lit search: Monoclonal antibody

Lit search: Steroid Implant for posterior uveitis

Original Articles

Books

Book Chapters

Electronic Articles

C. Stephen Foster, M.D.

ORDERING DETAILS INCLUDED

Foster CS, et al (Ed). 1972. The Epidemiology of Venous Thrombosis, Milband Memorial Fund Quarterly, Volume 1, Part 2.

Foster C.S., Sainz de la Maza, M. 1993. The Sclera. Springer-Verlag Publishers. New York. Out of Print. Can purchase as Used Book

Foster CS, Vitale A. 2001. Diagnosis and Treatment of Uveitis. WB Saunders, Philadelphia. Out of Print. In process of being Updated for new publication

Pleyer, Uwe; Foster, C. Stephen. Essentials in Ophthalmology: Uveitis and Immunological Disorders. 2007, XVIII, 231 p., 88 illus., 73 in colour, Hardcover. Click Here to Order

C. Stephen Foster, M.D.

Foster CS, Allansmith MR. 1979. Lack of Blood Group Antigen A on Human Corneal Endothelium. Immunology and Immunopathology of the Eye. (Eds. Silverstein, A.M., O’Connor, G.R.) Masson & Cie, New York. pp. 151-156.

Foster CS. 1982. Preocular Tear Film Abnormalities: Diagnosis and Treatment. Current Management in Ophthalmology. (Eds. Koch, D.D., Parke, DW., Paton, D.) Churchill-Livingstone, Inc., NY. pp. 25-55.

Foster CS. 1983. Corneal Manifestations of Neurologic Diseases. The Cornea. (Eds. Thoft, R.A., Smolin, G.) Little, Brown and Co., Boston, MA. pp. 315-328.

Foster CS. 1983. Ocular Manifestations of the Nonrheumatic Acquired Collagen Vascular Diseases. The Cornea. (Eds. Thoft, R.A., Smolin, G.) Little, Brown and Co., Boston, MA. pp. 264-284.

Foster CS. 1984. Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (formerly called Wegener’s). Current Ocular Therapy, 2nd ed. (Eds. Fraunfelder FT and Roy FH) W.B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia, PA. pp. 118-119.

Fujikawa LS, Bhan AK, Foster CS. 1984. T-Cell Subsets and Langerhans’ Cells in Conjunctival Lesions. Advances in Immunology and Immunopathology of the Eye (Ed. O’Connor, G.R.), Masson, New York. Chapter 13, pp. 43-47.

Foster CS, Wetzig R, Knipe D, Greene MI. 1985. Genetic Influence From Chromosome 12 on Murine Susceptibility to Herpes Simplex Keratitis. Herpetic Eye Diseases. (Eds. Maudgal PC and Missotten L) Dr. W. Junk. Pub., Dordrecht. pp. 67-76.

Foster CS. 1985. Systemic Immune Responses After Ocular Antigen Encounter. Herpetic Eye Diseases. (Eds. Maudgal PC and Missotten L) Dr. W. Junk Pub., Dordrecht. pp. 77-89.

Foster CS. 1986. Keratitis. Current Therapy in Infectious Disease. B.C. Decker, Inc., Philadelphia, PA. pp. 281-287.

Foster CS, Sonntag HG. 1986. Essentials of Microbiology in Uveitis. Uveitis: Pathophysiology and Therapy. (Eds. Kraus-MacKiw, E. and O’Connor, G.R.) Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc., NY. pp. 29-46.

Foster CS. 1987. Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory and Immunosuppressive Agents. Clinical Ophthalmic Pharmacology. (Eds. Lambert DW, Potter DE) Little, Brown, Inc., Boston, MA. pp. 173-192.

Foster CS, Mark DB. 1987. Corneoscleral Lacerations and Anterior Segment Reconstruction. Atlas of Ophthalmic Surgery Vol. II. (Eds. Heilmann K and Paton D.) Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc., New York. Chapter 5, pp. 1-48.

Foster CS. 1988. Basic Ocular Immunology. The Cornea. (Eds. Kaufman, H.E., et al.) Churchill Livingston, NY. pp. 85-122.

Foster CS, Jacobs DS, Reddy CV. 1992. Ocular Manifestations of Acquired Connective Tissue Disorders. Collagen Pathobiochemistry. Vol. 5. (Ed. Kang, AH., & J.B. Lippincott Co. Philadelphia). 161-180.

Foster CS. 1992. Fungal Keratitis. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America: Ocular Infections. (Eds. Michael Barza, M.D. and Jules Baum) 6:4;851-857.

Foster CS. 1990. Erythema Multiforme. The Eye in Systemic Disease. (eds. Gold DH, Weingeist TA). pp. 637-8.

Neves RA, Foster CS. 1994. Doen¨as Cicatriciais da Conjuntiva. Cornea. (eds. Belfort R and Kara-JosØ N). Editora Roca, Sùo Paulo, Brazil.

Foster CS. 1994. Chapter 70: Syphilis. Duane’s Foundations of Clinical Ophthalmology.(Tasman W and Jaeger EA, eds.) J.B. Lippincott Co., Philadelphia. 2:1-8.

Sainz de la Maza M, Foster CS. 1994. Chapter 23: Sclera. Duane’s Foundations of Clinical Ophthalmology (Tasman W Jaeger EA, eds.) J.B. Lippincott. 1:1-17.

Ayliffe W, Foster CS. 1995. Immune-Mediated Diseases of the Eye. Surgical Management in External Diseases of the Eye. (Stenson S, Ed) Igaku-Shoin, New York. pp. 239-302.

Foster CS. 1995. Chapter 27: The Eye in Skin and Mucous Membrane Disorders. Duane’s Foundations of Clinical Ophthalmology. (Tasman W and Jaeger EA, eds.) 5:1-41.

Tauber J, Foster CS. 1995. Cicatricial Pemphigoid. Eye and Skin Disease (Mannis MJ, Macsai MS and Huntley AC, Eds.). Raven Press. pp. 261-271.

Brody J, Foster CS. 1996. Vernal Conjunctivitis. Ocular Infection and Immunity. (Eds. Jay S. Pepose, Gary N. Holland and Kirk W. Wilhelmus). pp. 367-375.

Haimovici R, Foster CS. 1996. Sarcoidosis. Ocular Infection and Immunity. (Eds. Jay S. Pepose, Gary N. Holland and Kirk R. Wilhelmus). pp. 754-776.

Foster CS. 1996. Immunology of Infections. Infections of the Eye, 2nd Edition. (Tabbara KF and Hyndiuk RA, eds.) Little, Brown and Co. pp. 13-34.

Foster CS, Power WJ. 1996. Basic Ocular Immunology. In: Seminar in Ophthalmology, Uveitis and Ocular Inflammation; ( Friberg TR, Wu HK, eds.) W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia, PA. 11(1):3-9.

Foster CS. 1996. Autoimmune Uveitis. Current Therapy in Allergy, Immunology and Rheumatology, 5th Edition (Lichtenstein LM and Fauci AS, eds.). Mosby. Philadelphia, PA. 394-398.

Vitale A, Foster CS. 1997. The Pharmacology of Medical Therapy for Uveitis. Textbook of Ocular Pharmacology: Chapter 59: Corticosteroids. (Ed: Zimmerman TJ, Kooner KS, Shariv M, Fechtner RD) Lippincott Raven, Philadelphia p. 681-702.

Vitale A, Foster CS. 1997. The Pharmacology of Medical Therapy for Uveitis. Textbook of Ocular Pharmacology: Chapter 60: Mydriatic and Cycloplegic Agents. (Ed: Zimmerman TJ, Kooner KS, Shariv M, Fechtner RD) Lippincott Raven, Philadelphia p. 703-722.

Vitale A, Foster CS. 1997. The Pharmacology of Medical Therapy for Uveitis. Textbook of Ocular Pharmacology: Chapter 61: Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs. (Ed: Zimmerman TJ) Lippincott Raven, Philadelphia p. 681-702.

Vitale A, Foster CS. 1997. The Pharmacology of Medical Therapy for Uveitis. Textbook of Ocular Pharmacology: Chapter 62: Immunosuppressive Chemotherapy. (Ed: Zimmerman TJ, Kooner KS, Shariv M, Fechtner RD) Lippincott Raven p. 713-722.

Power WJ, Foster CS. 1998. Immunologic Diseases Affecting the Cornea. Corneal Diseases, Section IX, Chapter 18, 2nd ed. (Leibowitz HW, ed.).

Akpek EK, Merchant A, Pinar V, Foster CS. Ocular Rosacea: Patient Characteristics and Follow-up. 1998. Yearbook of Dermatology (Thiers BH and Lang PG, eds.)

Cockerham GC, Foster CS. 1999. Conjunctival Flaps. In: Brightbill FS, editor, Corneal Surgery: Theory, Technique and Tissue, 3rd edition. St. Louis: Mosby, Inc. pp. 135-141.

Rojas B, Foster CS. Cataract Surgery in Patients with Uveitis. 1999. The Oxford Textbook of Ophthalmology. (Easty D and Sparrow J, eds.) Oxford University Press.

Sainz de la Maza M, Foster CS. Scleritis and Episcleritis. 1999. The Oxford Textbook of Ophthalmology. (Easty D and Sparrow W, eds.) Oxford University Press.