- GENETIC MARKER

- GLAUCOMA

- GLAUCOMA, ANGLE CLOSURE (ACG)

- GLAUCOMA, OPEN ANGLE (OAG)

- GLAUCOMA, SECONDARY

- GLAUCOMA, UVEITIC

- GRANULOMATOUS

- HEALTH CONDITIONS ASSOCIATED WITH UVEITIS

- HEALTH TOPIC LINKS

- HLA-B27-ASSOCIATED UVEITIS

- HUMAN LEUKOCYTE ANTIGENS (HLA)

- HYPEROPIA

- HYPOPYON

- HYPOTONY

- IDIOPATHIC, IDIOPATHIC UVEITIS

- IMMUNE RESPONSE

- IMMUNE SYSTEM

- IMMUNOSUPPRESSIVE CHEMOTHERAPY

- INCIDENCE AND PREVALENCE OF UVEITIS

- INDIRECT OPHTHALMOSCOPE

- INFLAMMATION

- INTERMEDIATE UVEITIS

- INTRAOCULAR PRESSURE (IOP)

- IRIDOCYCLITIS

- IRIDOTOMY

- IRIS

- IRITIS

- JRA-ASSOCIATED UVEITIS (also called JIA-ASSOCIATED UVEITIS)

A specific tissue type or gene, similar to a blood type, that is passed on from parents to their children. Some genetic markers are, for example, linked to certain rheumatic diseases.

A–B–C–D–E–F–G–H–I–J–K–L–M–N–O–P–Q–R–S–T–U–V–W–X–Y–Z [Top]

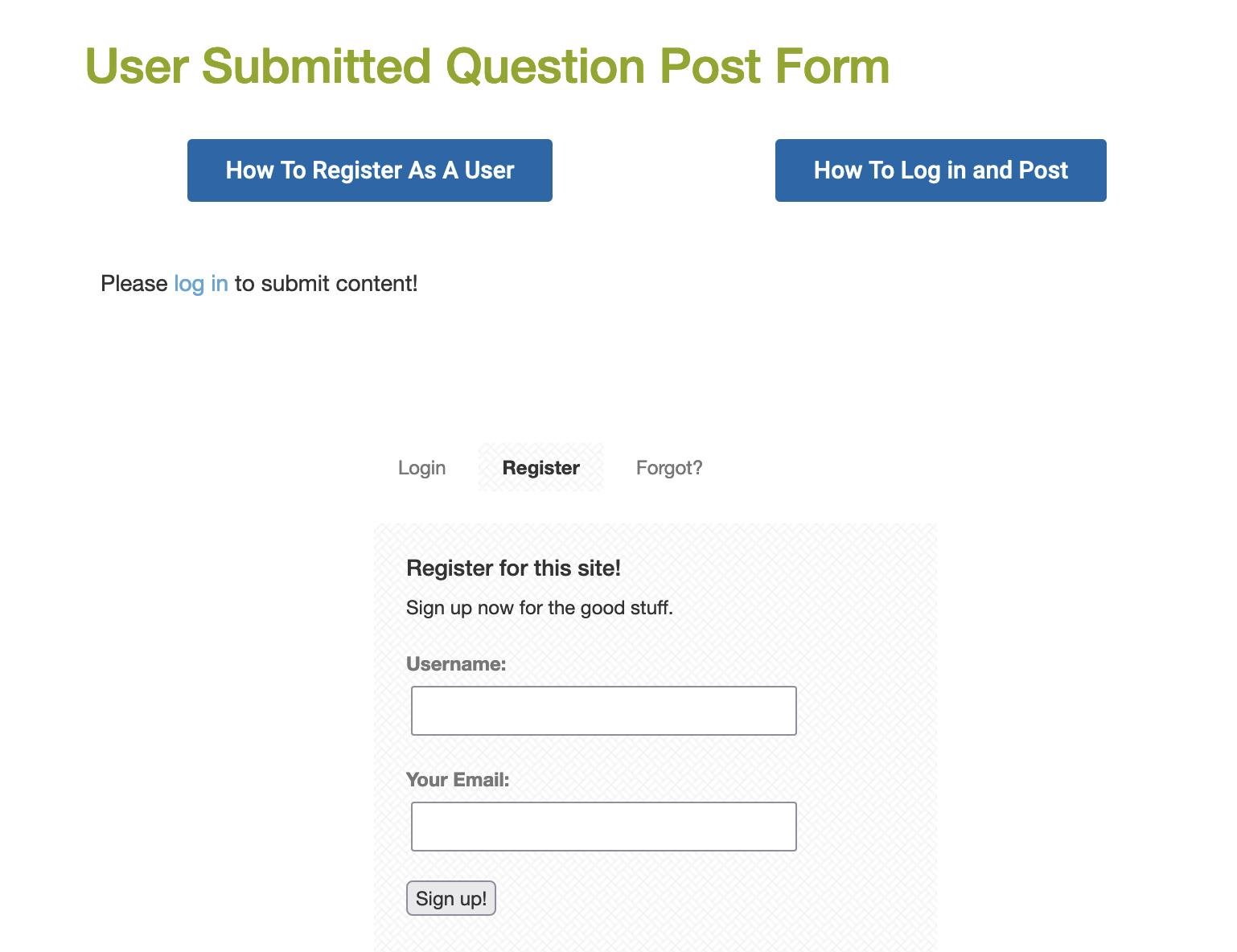

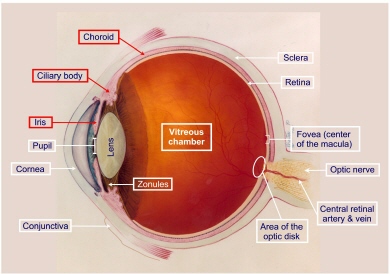

![]()

Photo of two optic nerves. The left is normal in appearance while the right is damaged by glaucoma. There is an expansion of the (yellow) cup area in glaucoma. This expansion represents the death of nerve cells. Without treatment, this damage expands and a slow tunneling of the side vision occurs.

Glaucoma is a condition characterized by vision loss due to irreversible damage to the optic nerve. Glaucoma, by accepted general definition, is damage to the optic nerve produced as a result of the imbalance between the blood flow (and the pressure driving it) to the optic nerve, and the pressure in the eye, which can reduce flow of blood to the optic nerve. In most instances, this imbalance of forces occurs as a result of pressure in the eye that is too high. The upper limits of normal is typically considered as 21 millimeters of mercury. Pressure above that without optic nerve damage is typically called “ocular hypertension.” Evidence of optic nerve damage, either through inspection of the nerve or through demonstration of abnormalities on visual field testing, is then defined as glaucoma.

Increased pressure occurs when the fluid within the eye, which is produced continuously, does not  drain properly. In the front of the eye is a space called the anterior chamber. A clear fluid, the aqueous humor, flows continuously in and out of this space and nourishes nearby tissues. The fluid leaves the anterior chamber at the angle where the cornea and iris meet. When the fluid reaches the angle, it flows through a spongy meshwork, like a drain, and leaves the eye.

drain properly. In the front of the eye is a space called the anterior chamber. A clear fluid, the aqueous humor, flows continuously in and out of this space and nourishes nearby tissues. The fluid leaves the anterior chamber at the angle where the cornea and iris meet. When the fluid reaches the angle, it flows through a spongy meshwork, like a drain, and leaves the eye.

Although normal pressure is usually between 12-21 mm Hg, a person might have glaucoma even if the pressure is in this range. That is why regular eye examinations, that includes pressure checks and examination of the optic nerve and vision field, are very important. Some groups are at increased risk for glaucoma and should be screened more frequently.

OPEN-ANGLE GLAUCOMA (OAG) gets its name because the angle that allows fluid to drain out of the anterior chamber is open. However, for unknown reasons, the fluid passes too slowly through the meshwork drain. As the fluid builds up, the pressure inside the eye rises. Unless the pressure at the front of the eye is controlled, it can damage the optic nerve and cause vision loss.

ANGLE-CLOSURE GLAUCOMA (ACG) is a condition in which the iris is apposed to the trabecular meshwork at the angle of the anterior chamber of the eye. When the iris is pushed or pulled anteriorly to block the trabecular meshwork, the outflow of aqueous from the eye is blocked, which causes a rise in intraocular pressure (IOP). If closure of the angle occurs suddenly, symptoms are severe and dramatic. Immediate treatment is essential to prevent damage to the optic nerve and loss of vision. If closure occurs intermittently or gradually, ACG may be confused with chronic open-angle glaucoma.

Although normal pressure is usually between 12-21 mm Hg, a person might have glaucoma even if the pressure is in this range. That is why regular eye examinations, that includes pressure checks and examination of the optic nerve and vision field, are very important. Some groups are at increased risk for glaucoma and should be screened more frequently.

Patients with uveitis are at increased risk of developing glaucoma because of the uveitis itself, and because of the use of corticosteroids which are the mainstay of uveitis treatment. When glaucoma is caused by other diseases or drugs, the condition is referred to as secondary glaucoma.The mechanisms by which uveitis leads to elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) are numerous and poorly understood. In general, Iridocyclitis affects both aqueous production and resistance to aqueous outflow, with the subsequent change in IOP representing a balance between these two factors. Inflammation of the ciliary body usually leads to reduced aqueous production, and combined with increased uveoscleral outflow often seen in inflammatory states, hypotony (low intraocular pressure) often is a consequence.

Prostaglandins, which have been demonstrated to be present in the aqueous of eyes with uveitis, are known to cause elevated IOP without a reduction in outflow facility. Mechanisms of increased resistance to aqueous outflow with both acute and sub acute forms of uveitis usually are of the open-angle type and include obstruction of the trabecular meshwork by inflammatory cells or fibrin, swelling or dysfunction of the trabecular lamellae or endothelium, and inflammatory precipitates on the meshwork. Uveitis also may be associated with secondary angle-closure glaucoma.

Alteration of the protein content of the aqueous humor may be a cause of elevated IOP in uveitis. Increased levels of protein in the aqueous are a result of increased permeability of the blood-aqueous barrier, which leads to an aqueous that more closely resembles undiluted serum. This elevated protein content may, in fact, lead to aqueous hypersecretion and IOP elevation.

And, the treatment of the uveitis can lead to elevated IOP. Although corticosteroids have proven effective in relieving inflammation, prolonged administration can result in elevated IOP. Corticosteroids increase IOP by decreasing aqueous outflow. Several theories have been proposed to explain this phenomenon, including accumulation of glycosaminoglycans in the trabecular meshwork, inhibition of phagocytosis by trabecular endothelial cells, and inhibition of synthesis of certain prostaglandins.

Text source, Uveitis & Glaucoma

|

|

| Simulation, normal visionSimulation, normal vision | Simulation, normal vision |

Click and Read: Uveitis and Glaucoma

Click and Read: Organizations

A–B–C–D–E–F–G–H–I–J–K–L–M–N–O–P–Q–R–S–T–U–V–W–X–Y–Z [Top]

Having the characteristics of a granuloma; nodular inflammatory lesions, usually small or granular, firm, persistent, and containing compactly grouped mononuclear phagocytes. Granulomatous inflammation is a distinctive type of chronic inflammatory reaction in which the predominant cell type is an activated macrophange with a modified epithelial-like appearance (epithelioid). A granuloma is a focal area of granulomatous inflammation consisting of an aggregation of macrophanges (some of which may be epithelioid cells or may fuse into syncytium-like multinucleated giant epithelioid cells), which may or may not be surrounded by a collar of mononuclear leukocytes, principally lymphocytes and occasionally plasma cells. Granulomatous inflammation is characteristic of certain diseases that result in the formation of granulomas in tissue: T.B., sarcoid, leprosy, etc.

A–B–C–D–E–F–G–H–I–J–K–L–M–N–O–P–Q–R–S–T–U–V–W–X–Y–Z [Top]

SELECT A HEALTH TOPIC:

See, also, list of Health Conditions Associated with Uveitis under the term, UVEITIS

A–B–C–D–E–F–G–H–I–J–K–L–M–N–O–P–Q–R–S–T–U–V–W–X–Y–Z [Top]

HLA-B27-associated uveitis occurs, we think, as a result of some germ or other triggering an autoimmune response. Certain germs have proteins that “look” like part of the HLA-B 27 protein that is present on the surface of the cells of the body in patients who inherit the HLA-B27 gene. And if such a person has the bad luck to come into contact with one of those certain germs at some point in life, the person’s immune system will, of course, attack and kill the germ; but it may also then inappropriately begin to “see” part of the HLA-B27 protein as also being foreign or germ-like, and attack it too, producing damage to the patient’s own cells. This then must be treated, calmed down, with steroids, and if it keeps coming back again and again, other medications may be needed as well.

Click and Read

A–B–C–D–E–F–G–H–I–J–K–L–M–N–O–P–Q–R–S–T–U–V–W–X–Y–Z [Top]

HUMAN LEUKOCYTE ANTIGENS (HLA)

The transplantation antigens (i.e., the antigens that are the major targets of immune rejection) of humans. These molecules have a role in regulating the immune response in general.

A–B–C–D–E–F–G–H–I–J–K–L–M–N–O–P–Q–R–S–T–U–V–W–X–Y–Z [Top]

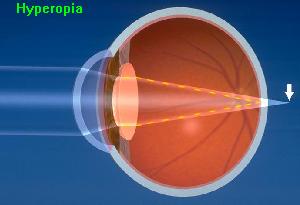

Farsightedness; ability to see distant objects more clearly than close objects; may be corrected with glasses or contact lenses. Farsightedness occurs if your eyeball is too short or the cornea has too little curvature, so light entering your eye is not focused correctly.

Farsightedness; ability to see distant objects more clearly than close objects; may be corrected with glasses or contact lenses. Farsightedness occurs if your eyeball is too short or the cornea has too little curvature, so light entering your eye is not focused correctly.

A–B–C–D–E–F–G–H–I–J–K–L–M–N–O–P–Q–R–S–T–U–V–W–X–Y–Z [Top]

Pus (white blood cells) in the anterior chamber.

Pus (white blood cells) in the anterior chamber.

A–B–C–D–E–F–G–H–I–J–K–L–M–N–O–P–Q–R–S–T–U–V–W–X–Y–Z [Top]

Low intraocular pressure. See, also, GLAUCOMA and IOP.

A–B–C–D–E–F–G–H–I–J–K–L–M–N–O–P–Q–R–S–T–U–V–W–X–Y–Z [Top]

IDIOPATHIC, IDIOPATHIC UVEITIS

There are at least one hundred known causes of uveitis. Many diseases that affect other parts of the body can cause uveitis. Examples include such autoimmune disorders as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, sarcoidosis, and inflammatory bowel disease. Some forms of cancer can cause uveitis. Infections such as TB and syphilis can cause uveitis. Injuries to the eye can cause inflammation to develop as well. Then, there is a whole category of uveitis called “idiopathic” — this basically means that the cause is unknown; that is, that the uveitis cannot be associated, at the time of evaluation, with a particular systemic illness. Since some systemic illnesses present first with symptoms only in the eyes, patients should be retested periodically for systemic illness if inflammation is persistent. So-called “idiopathic uveitis”, as with other forms of uveitis, can be difficult to treat and can be vision-robbing. See, also, classification of uveitis, and immunosuppression therapy.

See, also, UVEITIS.

A–B–C–D–E–F–G–H–I–J–K–L–M–N–O–P–Q–R–S–T–U–V–W–X–Y–Z [Top]

The reaction of the immune system against foreign substances. When this reaction occurs against substances or tissues within the body, it is called an autoimmune reaction.

A–B–C–D–E–F–G–H–I–J–K–L–M–N–O–P–Q–R–S–T–U–V–W–X–Y–Z [Top]

The immune system is a complex system that normally protects the body from infections. It combines groups of cells, the chemicals that control them, and the chemicals they release. The immune system is a complex network of specialized cells and organs that has evolved to defend the body against attacks by “foreign” invaders. When functioning properly, it fights off infections by agents such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. When it malfunctions, however, it can unleash a torrent of diseases, from allergy to cancer to uveitis.The immune system evolved because we live in a sea of microbes. Like man, these organisms are programmed to perpetuate themselves. The human body provides an ideal habitat for many of them and they try to break in; because the presence of these organisms is often harmful, the body’s immune system will attempt to bar their entry or, failing that, to seek out and destroy them. Sometimes the immune system’s recognition apparatus breaks down, and the body begins to manufacture antibodies and T cells directed against the body’s own constituents-cells, cell components, or specific organs. Such antibodies are known as autoantibodies, and the diseases they produce are called autoimmune diseases.

Uveitis on the basis of autoimmunity is the most common form of uveitis.

Watch this one minute video of a scene that could have come from science fiction as immune cells attack a harmless allergen as though it were a foreign invader.

Watch this one minute video of a scene that could have come from science fiction as immune cells attack a harmless allergen as though it were a foreign invader.

Click and Read

A–B–C–D–E–F–G–H–I–J–K–L–M–N–O–P–Q–R–S–T–U–V–W–X–Y–Z [Top]

IMMUNOSUPPRESSIVE CHEMOTHERAPY

There is a class of medications that gain their therapeutic effect by suppressing the immune system. Immunosuppressive therapy is also sometimes referred to as “chemotherapy” because some of the drugs in this class of medication were developed originally to fight cancer. The dose of these drugs, when used to treat inflammation inside the eye, is much smaller than the dose used to treat cancer. Children and adults are treated successfully with these medications for chronic eye inflammation that recurs upon withdrawal of steroid. Only physicians trained and experienced in the use of these medications should prescribe them.

The battle is long. The MERSI experience suggests that at least 2 years on immunomodulatory agents is necessary. The idea is to allow the patient’s immune system to re-learn how to behave itself properly instead of being hyperactive, inappropriate, or aggressive. Immunomodulation suppresses this over activity and inappropriateness, making (artificially) the immune system behave more normally. The goal of such treatment is not to over-suppress the immune system as is sometimes required in treating transplant or cancer patients; rather, the immune system is modulated, re-regulated, until it stops attacking the eye(s). Are there risks to this strategy? Sure. Are the risks worth taking? In the MERSI experience, absolutely. Because the risks are small and manageable if the medications are prescribed and monitored by an expert in these matters, and the benefits are enormous, i.e. preservation of sight and prevention of blindness for the rest of one’s life. Chronic steroid use ALWAYS causes damage. This is why doctors advocate getting away from that plan of treatment, and moving on to non-steroidal agents.

The goal of therapy is suppression of the immune inflammatory response, whether it is due to trauma, surgery, infection, or response to foreign or self-antigens, so that the integrity of ocular structures critical to good visual function is preserved. Any autoimmune disease affecting the eye, regardless of the form of autoimmunity, will require immunosuppressive therapy; the components of the immune system reside not in the eye, but rather are systemic, and therefore, regulation of those components will require systemic therapy. Such therapy is typically designed to suppress the overly aggressive immune system, allowing the body to eventually re-regulate itself, with the result often being that after the patient has been kept on systemic medications to suppress the inappropriate immune response for a finite length of time (for example, one year), medication can then be tapered and stopped without recurrence of the autoimmune attack. Sometimes resumption of the attack does occur, in which case the patient must be re-treated.

Immunosuppressive agents were, until recently, reserved for treatment of severe, sight-threatening, steroid-resistant uveitis or for use in patients who had developed unacceptable steroid-induced adverse effects. Now, instead of being regarded as merely steroid sparing, these drugs are often used as first-line agents for a variety of disease with destructive ocular sequelae. Patients must be adequately immunosuppressed yet be spared the potentially serious consequences of drug toxicity. In the hands of physicians trained in their use and monitoring, the administration of immunosuppressive agents appears to produce fewer serious adverse effects than does chronic use of systemic steroids. Immunosuppressive agents represent the final rung in our stepladder approach to the medical treatment of ocular inflammatory disease (see treatment algorithms).

The immunosuppressive drugs for which sufficient experience and information exists to warrant their use in treatment of ocular inflammatory conditions, by drug class, include the following: the alkylating agents (cyclophosphamide and chlorambucil), antimetabolites (azathioprine, methotrexate, leflunomide, and mycophenolate mofetil), antibiotics (cyclosporine-A, FK 506, sirolimus [rapamycin], and dapsone), receptor antagonists (etanercept and daclizamab [Zenapax] and immune-related adjuvants (bromocriptine, ketoconazole, and colchicine).

Click and Read

- AAO 200 Meetings: Ocular Inflammatory Disease

- Leukeran (Chlorambucil) Safe & Effective for Uveitis

- Methotrexate therapy for chronic non-infectious uveitis.

C. Michael Samson, MD, Nadia Waheed, MD, Stefanos Baltatzis, MD, and C. Stephen Foster, MD. (2001) Ophthalmology, 108: 1134-1139.

A–B–C–D–E–F–G–H–I–J–K–L–M–N–O–P–Q–R–S–T–U–V–W–X–Y–Z [Top]

INCIDENCE AND PREVALENCE OF UVEITIS

Uveitis is the third leading cause of blindness worldwide. Despite this fact, it is a relatively rare disease. In the Unites States, uveitis has an estimated prevalence of about 38 cases per 100,000 population, and an incidence of 15 cases per 100,000 population. It is estimated that uveitis afflicts 109,000 people in the U.S.and that 43,000 new cases a year are diagnosed. 2,359,242 people worldwide are estimated to have the disorder. Despite significant advances in research and therapeutics, the prevalence of blindness secondary to uveitis has not been reduced in the past thirty years; it remains the third leading cause of preventable blindness in the world. 10% will go blind if current trends hold. Recent (2001) epidemiological studies in the United States suggest that these figures may be underestimated by as much as 4 to 5 fold. The sight-threatening complications of uveitis include glaucoma, damage to the retina, and macular edema.

Uveitis in children: 5% to 10% of the cases of uveitis occur in children under the age of 16. But uveitis in children blinds a larger percentage of those affected than in adults, since 40% of the cases occurring in children are posterior uveitis, compared to the 20% of posterior uveitic cases in the adult uveitis population.There are, at any one time, approximately 11,000 cases of Pediatric Uveitis in the United States, with 4,300 new cases occurring each year.The sight-threatening complications of uveitis include glaucoma, damage to the retina, and macular edema.

Recent (2001) epidemiological studies in the United States suggest that these figures may be underestimated by as much as 4 to 5 fold.

Click and Read

A–B–C–D–E–F–G–H–I–J–K–L–M–N–O–P–Q–R–S–T–U–V–W–X–Y–Z [Top]

After the eyes are dilated, an indirect ophthalmoscope provides the physician with a wider view of the retina.

After the eyes are dilated, an indirect ophthalmoscope provides the physician with a wider view of the retina.

A–B–C–D–E–F–G–H–I–J–K–L–M–N–O–P–Q–R–S–T–U–V–W–X–Y–Z [Top]

Inflammation is a characteristic reaction of tissues to injury or disease. It is marked by four signs: swelling, redness, heat, and pain. When immune system cells and molecules invade tissues and organs as part of an immune system response, the collection of immune system cells and molecules at a target site is broadly referred to as inflammation.

Inflammation is a protective response. The ultimate goal of inflammation is to rid the individual of both the initial cause of cell injury (e.g., microbes and toxins) and the consequences of such injury, the necrotic cells and tissues. Inflammation and repair are closely intertwined. However, both inflammation and repair may be potentially harmful, as is commonly seen in allergic and autoimmune diseases. Components of both innate (essentially neutrophiles, other ganulocytes, macrophanges, and the complement system) and specific immunity (B and T lymphocytes through their antibodies and cytokines) may not only damage inflamed target issues but also may participate in the “innocent bystander injury” of surrounding normal tissues.

See, also, UVEITIS.

Click and Read

A–B–C–D–E–F–G–H–I–J–K–L–M–N–O–P–Q–R–S–T–U–V–W–X–Y–Z [Top]

Intermediate uveitis is inflammation predominantly located in the anterior part (toward the front) of the vitreous. It is a common type of uveitis in children and young adults. Although the majority of cases are idiopathic and the patients have no systemic disease, a significant association between intermediate uveitis and sarcoidosis, multiple sclerosis (MS ), and Lyme disease is widely accepted. See, also, classification of uveitis. The International Uveitis Study Group classification schema for uveitis has been widely adopted for clinical and research purposes. It separates uveitis by anatomical location of the disease, according to the major visible signs, in the various segments of the eye: anterior uveitis, intermediate uveitis, posterior uveitis, and panuveitis.

Intermediate uveitis is inflammation predominantly located in the anterior part (toward the front) of the vitreous. It is a common type of uveitis in children and young adults. Although the majority of cases are idiopathic and the patients have no systemic disease, a significant association between intermediate uveitis and sarcoidosis, multiple sclerosis (MS ), and Lyme disease is widely accepted. See, also, classification of uveitis. The International Uveitis Study Group classification schema for uveitis has been widely adopted for clinical and research purposes. It separates uveitis by anatomical location of the disease, according to the major visible signs, in the various segments of the eye: anterior uveitis, intermediate uveitis, posterior uveitis, and panuveitis.

The term intermediate uveitis (IU) was suggested by the International Uveitis Study Group (IUSG) to denote an idiopathic inflammatory syndrome, mainly involving the anterior vitreous, peripheral retina, and ciliary body, with minimal or no anterior segment or chorioretinal inflammatory signs. Other names previously used in the literature to describe this entity include chronic cyclitis, peripheral uveitis, vitritis, cyclochorioretinitis, chronic posterior cyclitis and peripheral uveoretinitis. IU may or may not be associated with specific infections (Lyme disease, toxocariasis, Whipple’s disease, cat-scratch disease) and noninfectious diseases (multiple sclerosis and sarcoidosis). The term pars planitis has been retained and used to describe the characteristic exudates that can be seen on the pars plana in some patients with IU, and may or may not represent a distinct clinical entity.

IU ha been reported in 8% to 22% of uveitis patients. Of 1,237 patients with uveitis referred to the Immunology and Uveitis Service of the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary over a 10-year period, 162 (13%) were classified as IU. The disease seems to affect patients primarily from childhood through the fourth decade, but it has also been reported in older patients. There seems to be no clear gender or race predilection. Approximately 70% to 90% of cases are bilateral, albeit asymmetric, with symptoms frequently being confined to one eye.

Despite the fact that many studies suggest that IU tends to be one of the most benign forms of uveitis, severe complications secondary to chronic, indolent inflammation may arise, which may eventuate in blindness. Even the authors who emphasize the generally good prognosis of this disease admit that 20% of patients have visual acuity of less than 20/40. Ocular hypertension, sometimes leading to glaucoma, has been reported in approximately 8% of patients with IU. In most cases, this ocular hypertension seems to be corticosteroid induced. Cataract formation is found in approximately 50% of patients with intermediate uveitis. Previous studies suggest that cataract formation tends to be less severe in patients who have been treated early with immunosuppressive drugs, rather than corticosteroids. Retinal detachment may occur in patient with IU (5% to 17%). Optic nerve involvement is not uncommon in IU (3% to 20%) and is observed more often in children than adults. Multiple sclerosis (MS) has been reported to develop in 7.4% of patients with pars planitis.

See, also, UVEITIS.

Click and Read

A–B–C–D–E–F–G–H–I–J–K–L–M–N–O–P–Q–R–S–T–U–V–W–X–Y–Z [Top]

A measure of the pressure inside the eye; normal IOP varies among individuals.Intraocular pressures is measured using a tonometer. Although normal pressure is usually between 12-21 mm Hg, a person might have glaucoma even if the pressure is in this range.

A measure of the pressure inside the eye; normal IOP varies among individuals.Intraocular pressures is measured using a tonometer. Although normal pressure is usually between 12-21 mm Hg, a person might have glaucoma even if the pressure is in this range.

The IOP in patients with active uveitis is most commonly decreased owing to impaired production of aqueous by the nonpigmented ciliary body epithelium. This however, is not always true because final IOP is also based on the facility of outflow and episcleral venous pressure. It is the balance of these factors that determines the ultimate IOP (see GLAUCOMA).

Factors that can affect IOP include the accumulation of inflammatory material and debris in the trabecular meshwork with obstruction of aqueous outflow, inflammation of the trabecular meshwork (trabeculitis), obstruction of venous return, and steroid therapy. For unknown reasons, elevated IOP is frequently associated with infectious uveitis, for example, herpetic uveitis. Repeat measurements should be taken at each visit because the effects of uveitis on IOP can vary over the course of the inflammatory episode.

Click and Read

A–B–C–D–E–F–G–H–I–J–K–L–M–N–O–P–Q–R–S–T–U–V–W–X–Y–Z [Top]

Iridocyclitis is a term used to denote inflammation in two parts ofthe uveal tract of the eye; the iris and the ciliary body. It derives its name from combining iritis (inflammation of the iris) and cyclitis (inflammation of the ciliary body). Iridocyclitis may also be referred to as anterior uveitis, or a form of intermediate uveitis, depending upon the classification system employed by the physician.Chronic, nongranulomatous Iridocyclitis is an important complication of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis.

See, also, UVEITIS.

A–B–C–D–E–F–G–H–I–J–K–L–M–N–O–P–Q–R–S–T–U–V–W–X–Y–Z [Top]

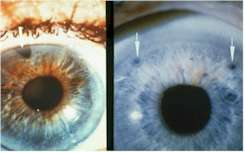

An iridotomy is an opening created in the iris, usually by a laser, sometimes by surgery. The most common reason for its placement is an acute attack of narrow angle glaucoma or the risk of such an attack. Over time, some iridotomies close due the normal healing process. If this occurs, the procedure may need to be repeated. Patients with uveitis or cataract my require other types of surgery to control glaucoma. Arrows point to iridotomy openings

An iridotomy is an opening created in the iris, usually by a laser, sometimes by surgery. The most common reason for its placement is an acute attack of narrow angle glaucoma or the risk of such an attack. Over time, some iridotomies close due the normal healing process. If this occurs, the procedure may need to be repeated. Patients with uveitis or cataract my require other types of surgery to control glaucoma. Arrows point to iridotomy openings

A–B–C–D–E–F–G–H–I–J–K–L–M–N–O–P–Q–R–S–T–U–V–W–X–Y–Z [Top]

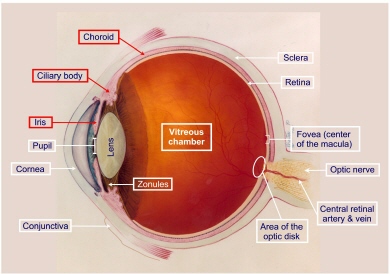

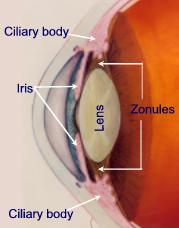

The iris is the most anterior part of the uvea. It is the colored ring of tissue suspended behind the cornea and immediately in front of the lens. It lies between the anterior and posterior chamber and is suspended in aqueous humor. It regulates the amount of light entering the eye by adjusting the size of the pupil. The iris, which measures about 12 mm in diameter and has a circumference of 28 mm, is thickest (0.6 mm) at the pupillary margin, and is thinnest (0.5 mm) at the ciliary margin. The pupillary margin of the iris rests lightly on the anterior surface of the lens. The iris root is attached to the ciliary body.

When we say that someone has “green”, or “brown”, or “blue” eyes, we are describing the color of the iris. Iris color varies from light blue to dark brown, depending on the amount of pigment produced in the melanocytes. The blue color results from the absorption of light with long wavelengths and the reflection of shorter blue waves, which can be seen by the observer. The iris color is inherited.

A–B–C–D–E–F–G–H–I–J–K–L–M–N–O–P–Q–R–S–T–U–V–W–X–Y–Z [Top]

Iritis is inflammation predominantly located in the iris of the eye. Inflammation in the iris is more correctly classified as anterior uveitis because there is also, often, inflammation of the ciliary body.

Iritis is inflammation predominantly located in the iris of the eye. Inflammation in the iris is more correctly classified as anterior uveitis because there is also, often, inflammation of the ciliary body.

When the iris is inflamed, white blood cells (leukocytes) are shed into the anterior chamber of the eye where they can be observed on slit lamp examination floating in the convection currents of the aqueous humor. These cells can be counted and form the basis for rating the degree of inflammation.

See, also, UVEITIS.