Uveitis is the third leading cause of blindness in America, and 5% to 10% of the cases occur in children under the age of 16. But Uveitis in children blinds a larger percentage of those affected than in adults, since 40% of the cases occurring in children are posterior uveitis, compared to the 20% of posterior Uveitic cases in the adult Uveitis population.

There are, at any one time, approximately 115,000 cases of Pediatric Uveitis in the United States, with 2,250 new cases occurring each year. Spread across the entire U.S. population, therefore, and across all offices of Ophthalmic practitioners, the likelihood that any one individual practitioner will care for a patient with Pediatric Uveitis is relatively small, and the likelihood that any single individual will have significant experience in caring for large numbers of cases over a long period of time is vanishingly small. This accounts, we believe, at least in part for the sub-optimal care that many of our children with Uveitis appear to be receiving, even in these “modern” times. The stakes are incredibly high, for the child, for the parents who will be faced with (usually) many years of dealing with this health problem in their child, and for society at large because of the life-time of dependence which occurs in those who eventually reap substantial visual handicap as the result of sub-optimal treatment.

We believe that current epidemiologic data emphasize two critically important goals for all of us in Ophthalmology, acting together, in an effort to change the current prevalence of blindness caused by Pediatric Uveitis:

- Repeatedly emphasizing to parents, other medical colleagues, especially Pediatricians, and school personnel the critical importance of routine (annual) vision screening for all children.

- The critical importance of beating back the frontiers of general ignorance and mind sets, eliminating the all-too-common pronouncement by physicians to parents of a child with Pediatric Uveitis that:

- “He’ll (She’ll) out grow it.”

- “The drops will get him (her) through it.”

- “It’s just the eye; systemic therapy is not warranted.”

Statements (a) and (b) are true, but too often pull the doctor, and patient, and family into the seduction of nearly endless amounts of topical steroid therapy. It is generally true that the child will in fact “out grow” the Uveitis, i.e., that the Uveitis will no longer be a problem eventually. The pity is, however, that so often by the time the child “out grows it”, permanent structural damage to retina, optic nerve, or aqueous outflow pathways has already occurred, and the blinding consequences are now permanent. It is also true that for any individual episode of Uveitis, the steroid drops usually will get the patient through it. But the fact is that so many children with Pediatric Uveitis have recurrent episodes of Uveitis such that the cumulative damage caused by each episode of Uveitis and the steroid therapy for each episode eventually produces vision-robbing damage. And item (c) is simply the result of the common myopic viewpoint of Ophthalmologists: that it is just an eye problem, and therefore should simply be treated with eye medications. Nothing could be further from the truth! And unless and until large numbers of Ophthalmologists reframe this socially and epidemiologically important matter, the prevalence of blindness secondary to Pediatric Uveitis is not going to change.

The differential diagnosis of Pediatric Uveitis is relatively vast, and therefore the detective work required to properly pursue the underlying diagnosis is complex. The job can be slightly simplified by “playing the odds”, categorizing the case as carefully as possible into anterior non-granulomatous; anterior granulomatous; intermediate; posterior, with vasculitis; posterior, without vasculitis; and categorizing it into the general age groups of Infancy (0 to 2 years), Toddler-School Age (2 to 10 years), and Adolescence (10 to 20 years).

The most common etiologic groups in children segregated into these groups are shown in Tables 1-6

TABLE 1 (Anterior Non-Granulomatous)

Idiopathic

HLA-B27 associated

Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis

Ankylosing Spondylitis

Reactive Arthritis (formerly called Reiter’s syndrome) disease

Psoriasis

Inflammatory bowel disease

Nephritis

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Herpes Simplex virus

Lyme disease

Leukemia

Drug-induced

TABLE 2 (Anterior Granulomatous Uveitis)

Sarcoidosis

Inflammatory bowel disease

Syphilis

Herpes simplex virus

Tuberculosis

Bechet’s disease

Multiple Sclerosis

Fungal disease

Whipple’s disease

Leprosy

TABLE 3 (Intermediate Uveitis)

JRA

Pars Planitis

Multiple Sclerosis

Lyme disease

Sarcoidosis

TABLE 4 (Posterior Uveitis, without vasculitis)

Toxocariasis

Toxoplasmosis

Leukemia

Tuberculosis

Intraocular Foreign Body

Vogt-Koyanagi Harada Syndrome

TABLE 5 (POSTERIOR UVEITIS, with vasculitis)

Posterior Uveitis with vasculitis

Cytomegalovirus

HSV/VZV

Inflammatory bowel disease

Syphilis

Bechet’s disease

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Kowasaki’s disease

Sarcoidosis

Polyarteritis nodosa

Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (formerly called Wegener’s)

TABLE 6 (most common causes of Uveitis in infants)

Herpes Simplex Virus

Toxocara

Congenital Loes

Retinoblastoma

TABLE 7 (most common causes of Uveitis in Toddlers/School Children)

Toxocariasis

Toxoplasmosis

Leukemia

Vogt-Koyanagi Harada Syndrome

Diffuse Unilateral Sclerosing Neuroretinitis

Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis

TABLE 8 (most common causes in Adolescents)

JRA

Pars Planitis

VKH

Toxoplasmosis

HLA-B27-associated sarcoidosis

Bechet’s disease

Intraocular Foreign Body

We believe that aggressive efforts should be made to uncover the underlying cause of Uveitis in any child. If the review of systems is negative and the patient has non-recurrent anterior granulomatous Uveitis, we would not do laboratory studies. However, if review of systems is positive, we would “follow the review of systems”.

For recurrent anterior non-granulomatous Uveitis we would obtain a complete blood count and urine analysis, ANA testing, HLA-B27 testing, and would “follow the review of systems”.

The diagnostic step ladder in a pediatric patient with anterior granulomatous Uveitis, recurrent or not, would include a CBC with urine analysis, and FTA-ABS testing, Lyme disease antibody and western block, PPD analysis, chest X-ray, ANA, and angiotensin converting enzyme determination. Chest CT, and Gallium scanning would be pursued if diagnosis of sarcoidosis was strongly suspected, and, of course as usual, we would “follow the review of systems positives”.

In a patient with intermediate Uveitis, all would deserve laboratory evaluation, including CBC, urine analysis, chest X-ray, FTA-ABS, ACE, PPD, Lyme, and ANA titers.

Any patients with posterior Uveitis would deserve an extensive vasculitis work-up, if vasculitis were present, and a search for “the usual suspects” with an eye to an infectious etiology, such as that producing a granuloma in the choroid in a patient with toxocariasis or Toxoplasmosis. An audiogram or lumbar puncture would be done if positive on the review of systems were found such as tinnitus and/or meningeal signs or symptoms. Finally, a diagnostic vitrectomy would be added to the step ladder in a patient with posterior Uveitis if all non-invasive studies were unrevealing and the case was difficult to treat successfully.

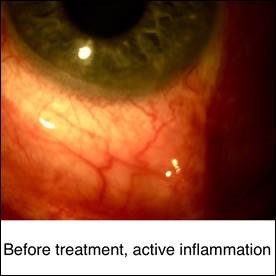

On the matter of treatment, here too we believe strongly in the step ladder approach, always beginning with steroids, in any route required to achieve the desired goal, i.e., abolition of all active inflammation. Topical steroids would be followed by an examination under anesthesia with regional steroid injection therapy in a patient with granulomatous or non-granulomatous anterior Uveitis. Systemic steroids would be employed in the event that this approach did not achieve the goal of abolition of all active cells. We are extremely reluctant to get involved with long term daily systemic steroid use in a youngster, because of the obvious growth-retarding properties of such therapy. But long term oral non-steroid anti-inflammatory drug therapy, managed by a Pediatrician, can be extremely successful, in our experience in approximately 70% of children with recurrent non-granulomatous anterior Uveitis. If this strategy is not successful, then consideration of once weekly, low-dose, Methotrexate or daily Cyclosporine or CellCept would be the next considerations.

In granulomatous disease topical steroids often are not sufficient, and systemic therapy, particularly with oral non-steroidal inflammatory drugs, may be utilized sooner rather than later.

With Intermediate Uveitis topical steroids are not effective in penetrating to the level of inflammatory focus. Regional steroid injections or systemic steroids are employed to treat that area, sometimes with adjunctive topical steroids for anterior chamber “spill over” reaction. Retinal Cyropexy can be effective in selected cases of recurrent Pars Planitis, as can therapeutic Pars Plana Vitrectomy. Systemic immunomodulatory therapy, as usual, represents the final step in the step ladder approach in the aggressiveness of care.

Patients with Posterior Uveitis of course do not respond to topical therapy and therefore require systemic steroids and/or immunomodulators right from the very beginning.

We hope that this will provide some help to those Ophthalmologists who have also concluded that the usual approach to Pediatric Uveitis, i.e., steroid drops, is not always sufficient, but who are hesitant to take the initiative to commit the patient to more aggressive treatment.